In the midst of running around looking for fuel in a harried Lagos metropolis, I couldn’t focus on Mr. Otedola’s letter to his bosom friend, Aliko Dangote.

People kept sending it to me as if they were reporting him for some misdeed. I would see “my dear friend Aliko,” and just in time, I’d look away to avoid slapping someone in the queue who had just hit my bumper.

After two days of searching for fuel, which finally ended with a N75,000 purchase instead of the usual N30,000, I took a breather and opened the letter.

I glanced through it, much like you skim through wedding or birthday tributes, not wanting to waste time before the food is gone. But then something caught my attention.

Both men had once tried to buy one of the rundown national refineries, with Aliko holding about 50% and Otedola another 20%.

That’s true. I was very aware of that transaction because, at BGL, where I worked at the time, it was a poster transaction.

Our boss, Albert Okumagba, was part of that deal, and I can still remember his upbeat excitement when it was cancelled by the fledgling Yar’Adua administration.

Albert looked me in the eye and said, “They have triggered Alhaji, and he will do something massive in that space very soon.”

Sadly, Albert did not live to see the day when the first tankers of fuel rolled out of the expansive refinery complex that must have been conceived the day Yar’Adua cancelled the other transaction.

In his letter, Mr. Otedola was quite effusive as he went on to praise his friend not only for this achievement but also for his other feats, especially in the cement industry.

Aliko Dangote is not ordinary. He is made from the same strain that produced the Rockefellers and all those great men who pulled America out of the Great Depression.

Or how else do you describe a man who, in one fell swoop, is one of the largest employers of labor, one of the biggest taxpayers, and has significantly impacted major industries, changing narratives and forcing a paradigm shift at the same time?

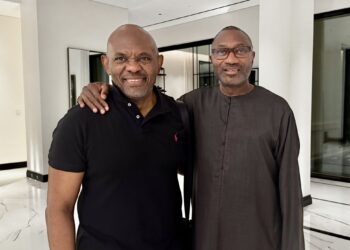

You see Otedola boasting like a little boy in Shomolu whose father just bought the first motorbike in the neighbourhood.

“Go turn your tank farms to scrap, go shut down your facilities because a bigger king has come,” he deadpans.

True, Aliko’s refinery has rendered a whole substructure moribund. It has achieved a warship turnaround, something that is almost impossible.

Today, the giant National Oil Company, which just a few months ago was locking horns and sending dissonant signals about its inability to deliver, is now shoving everybody aside to be the sole off-taker of his fuel.

This was not just a dream. It was an addiction. He was addicted to the dream of delivering this refinery.

We saw him grow grey, we saw him getting bent, we saw the stress on his face as he started wearing dark goggles—perhaps to hide his tired and worried eyes—but he kept pushing, together with his team. And today, one single man is about to pull 200 million people out of a certain rudderless future.

This event is not just a testament to the very strong will of this Nigerian; it also serves as a lightning rod of inspiration as to what we can achieve if we truly set our minds to it.

This is a clarion call, and there is not much more to be said.

Well done, sir.

Duke of Shomolu