Often, I try to write in a manner that is neutral wherein I stack up facts to lead to an outcome. Today, I will be breaking that rule to act as an active participant in this piece. Nigeria faces a crisis and our policymakers must make bold decisions some of which will be bitter. This requires the right mix of courage and focused thinking with sustainability in mind.

We are living in an unusual time. The world as we know it is going through a tumultuous change brought about by the COVID-19 outbreak. As most countries hunker down into some form of isolation to battle the epidemic, financial markets have been hit by a severe bout of risk-off sentiments which has led to steep declines in asset prices across major economies.

Against this backdrop is the breakdown of the alliance between Russia and Saudi Arabia, that has fueled a dramatic collapse in oil prices. Brent crude prices, the global benchmark has dropped by around half of its price at the start of 2020 to under USD28-29/bbl.

Coming at a time the COVID-19 virus is making landfall in Nigeria with a pick-up in infections, we face the prospect of fighting battles on two fronts (health and economics) with inadequate foreign reserves and a weak healthcare system. It is worth remembering that in 2016 when Brent crude prices tumbled by slightly over 50%, Nigeria’s oil exports (90% of total exports) dropped from over USD90 billion to a low of USD32 billion in 2016.

READ MORE: China lends helping hand, as Nigeria seeks support to curb coronavirus

This filtered through to government accounts where oil share of revenues which averaged 70-75% of total revenues hit a bottom of 37% in 2016. The economy went into a deep recession and the Naira lost over half of its value over the period In the event, that crude oil prices remain at present levels for the next 4-6months, Nigeria faces the prospect of a current account deficit likely in the region of USD15-20 billion and a potential fiscal imbalance in excess of NGN4.5 trillion.

The latter number excludes state-level revenue shortfalls due to over-reliance on distributions from the Abuja. The economic forecast appears largely gloomy. The challenge before Nigerian policy markers is daunting and dealing with these shocks requires a combination of courage and clear-thinking.

In the absence of fiscal buffers, we will need to raise a non-trivial amount of money to mitigate this shock. The Nigerian state will need to find a way to raise a large amount of money and we do not have to be ashamed about it. By my estimates, the dual COVID-19 and oil price shock has created a large financing requirement of around USD15-20 billion.

Plugging this gap will require a combination of debt, equity and some currency adjustment. Presently, global debt markets are in a freeze and even when they eventually re-open, Eurobond debt of oil-exporting frontier market countries are likely to be out of favour unless it comes at extremely high-interest rate levels.

To convince anyone local or foreign to fund this gap, Nigeria needs to credibly demonstrate that these monies will go some way towards fixing the structural issues that have left her vulnerable to external shocks.

Design and start implementation of a credible economic reform plan. There is no point raising a ton of cash with no strategic plan on how to deploy it in a sensible manner that mitigates the economic shocks. Nigeria needs a well-thought-out and credible economic plan.

Unlike the last such plan (ERGP), which was designed by outside experts and not embraced by the government, this new plan should be spearheaded by the increasingly credible Presidential Economic Advisory Council (PEAC) ably supported by the finance ministry and the CBN. This plan should include clear policies to adopt with specific outcomes.

At the minimum it should include completing long-delayed public financial management reforms (which have gone on for far too long) at federal (and state level), improving tax collection, improving monetary policy and resuming the suspended privatization/liberalization program.

Already, we have kick-started this process with the introduction of price modulation in the energy sector (which looks like quasi-deregulation) and it is refreshing to see the CBN has allowed the Naira adjust slightly to sizable external pressures. Put together within a coherent economic plan designed and led by the now credible PEAC, Nigeria could buy some credibility with local and foreign financiers to avail her the much-needed cash pile to ride out this storm.

[READ MORE: Four ways Nigerian government can minimize impact of COVID-19)

Time to open up new sectors for private capital. For far too long Nigeria has relied on the debt financing as a means of plugging budget holes which have resulted in high debt service to revenue ratios which are clearly unsustainable.

Now is the time for Nigeria to sell some equity to plug its fiscal hole and resume the stalled privatization/liberalization programs of the 2000s. To be clear, one need not embark on a fire-sale program of state assets but rather a disciplined approach towards opening-up moribund sectors of the economy to private capital, alongside a sell-down of controlling stakes in certain sectors and/or concessions of key public corporations to improve operational efficiency.

Nigeria unlocked the telecommunications sector in the 2000s and is mid-way through fixing its thorny power sector problems. Fixing the tariff issues and tighter regulation of distribution companies should drive further improvements but there can be no progress without privatization of the Transmission Company of Nigeria (TCN).

Over the last four years, the FGN has tried to invest in transmission from its balance sheet with limited success. I believe now is the time to sell-down government interest there to private capital.

This should be accompanied by reforms aimed at the distribution companies which will seek to break the link between the exchange rate and electricity tariffs by pushing the discos raise fresh equity to pay down legacy USD loans and allowing them charge tariffs more reflective of the underlying costs they face.

Fixing the mid and downstream issues of the power sector will require less government involvement and more private capital. Beyond the power sector, Nigeria can look to concession or sell-down equity holdings in the transport sector: airports, railways and seaports.

Nigeria also has a postal service where government does not need to own a 100% stake, we can sell down to under 50%, but management should be outsourced to the private sector. Notice, I’ve avoided talk about the key juicy assets in the energy sector. Focus should be on opening up closed off sectors to private capital to unlock new sectors for future growth.

Then the difficult debt discussion. Nigeria will need to borrow in the right combination of USD and NGN debt in a manner that is fiscally sustainable. For a start the FGN can tap local debt markets where thanks to the CBN action in 2019, local non-bank investors are sitting on a large liquidity pile which can be deployed towards plugging the fiscal hole.

In the press release following the meeting with the PEAC, there was talk about securitizing the FGN debt on CBN’s balance sheet. To ensure fiscal sustainability these NGN debt instruments can be structured as long tenored zero-coupon bonds with annual interest expense commitment but priced at a discount that offers a positive real yield over long term inflation and programmed to mature in a year with no FGN bond maturities.

The USD leg is where Nigeria will need a combination of Eurobond debt sales and some multilateral financing. If Nigerian shows some traction by going through with reform and liberalization, we could just buy enough credibility to obtain concessionary financing as we have effectively posted our credibility upfront.

In the event that our case is more dire, Nigeria could tap the IMF for a standby arrangement (SBA) wherein we do not exactly borrow any money but buy the cover of IMF protection (which is triggered in the event of a balance of payment crisis) by committing to a set of reforms.

This is more sensible if the reforms proposed fit the ones designed by the PEAC and we commit to them. Optically, we are not increasing our debt burden and also not actually implementing any IMF plans, but economic policies designed by Nigeria’s brightest economists.

In the near term, Nigeria should look to tap available COVID-19 funding to reform Nigerian healthcare. Amid the COVID-19 crisis, several multilateral development organizations ave announced the provision of large pools of concessionary financing which I strongly believe that our economic managers should commence talks about access.

The health care system is clearly unable to handle a large break-out of COVID-19 and as such tapping these pools and dedicating these funds towards expanding hospital capacity on a national scale, increasing production of standard drugs and medical supplies and catalyzing local patient capital into the healthcare sector is a good start.

We can use this crisis to start a pension-style health insurance coverage system that pools available funding by Nigerians for healthcare. Basically, let’s use this window to institute a contributory health insurance scheme with savings managed by private health care providers just as we have with pensions.

Reforming the badly broken national health insurance scheme and replacing it with a private sector-led system will sort out the demand side for healthcare services. These pools will readily provide the purchasing power required for providers of institutional-grade quality healthcare services to scale up.

Under the cover of reforming Nigerian healthcare to fight the COVID, our policymakers can lay out a credible plan for donors to provide concessionary financing to fix our healthcare system. Those dollars will also come in handy in shoring up external imbalances.

Longer-term, the government needs to improve the supply of bankable infrastructure assets across a host of sectors outside healthcare. While there exists strong demand for infrastructure assets by local pension funds, the supply of bankable infrastructure assets is lacking.

The reason is simple: The Nigerian government at Federal and State levels own the legal rights to most brownfield infrastructure assets (i.e. infrastructure projects with strong revenue-generating potential) and appears reluctant to concession these assets to private managers.

Rather the government always appears keen on pushing private capital towards assuming more riskier greenfield projects. In an environment where government has a long track record of ripping up agreements, this means termination risk on Greenfield projects is way too much for retirement savings without greater controls by fund managers.

As always solving this time-inconsistency problem involves government posting its credibility upfront by using proof of concept with easier brownfield projects or relying on guarantees. The issue with guarantees though is they remain restricted to only projects on the table.

To break the cycle, Nigeria needs to identify say 36 high-value projects (across the six geopolitical regions) and seed these assets to infrastructure asset managers to package into a fund to catalyse institutional finance.

We must replace the current build-as-you-fund approach by leveraging fiscal balance sheets with one which involves a clever mixture of construction financing, local pension fund money and development finance institutions. This requires the government be ready to let go of control and allow the delivery of certain classes of infrastructure (e.g tollable roads) be private sector managed. This will go a long way towards catalyzing a fully functional infrastructure market.

[READ ALSO: COVID-19, a virus that shakes global financial markets)

In the early 1980s, oil prices collapsed as the OPEC alliance broke down and Saudi Arabia ramped up production to punish other members of the cartel (like Nigeria) who reneged on agreed production quotas. Around this period, a certain army general came to power in Nigeria and adopted a radical economic restructuring plan to cope with the oil price pain.

Unfortunately, he was ousted by the very team that brought him to power as his austere plans proved too difficult to digest. In 2015, after his victory at the presidential elections, that army officer, now retired, once again faced up to the prospect of low oil prices again. His attempt at retaining the status quo to avoid a repeat of his 1980s debacle led Nigeria into a deep recession.

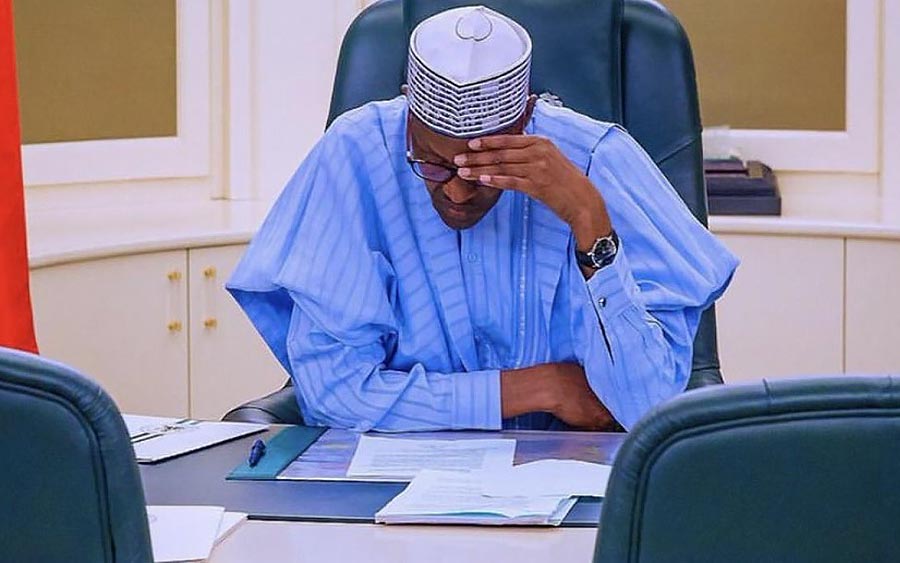

In 2020, lightning appears to have struck thrice and or as someone put it: life has thrown President Muhammadu Buhari another chance to leave a more lasting positive imprint on Nigeria’s economic structure. He has no more elections to run and he has all the political capital to drive reforms to allow private capital to gain a foothold over larger sections of the economy than ever before.

I have become a follower of nairametrics because of the brilliant write-ups that is published. I appreciate your work. I have a slight trouble on the how, you didn’t address a very important part. How can we implement anything reasonable when the law makers are majority of people that will rather show off their four wives n tell us about their numerous children that they plan to send abroad with the remainder of the oil money.