With 80 percent of inmates in the Nigerian prisons awaiting trial, there is a likelihood that inmates die before they get a due hearing before the court. Some detainees have spent over 10 years behind the prison walls without trial for minor offences. Gavel is a civic-tech organization which intends to put an end to the problem of delayed trial and unjust incarceration. Aimed at improving the pace of justice delivery through technology, the startup also provide free legal service to poor inmates.

In a chat with Nairametrics’ Managing Editor, Omotola Omolayo, the founder of Gavel, Nelson Olanipekun shares the company’s vision and why the Nigerian justice system in the country needs an overhaul.

Omotola Omolayo (OO): What informed your choice of profession?

Nelson Olanipekun (NO): Personal reasons; my dad ran a business when we were young. As a businessman, you will have loans from banks. At a point, he had issues with the bank. The interest charges were too high and the business was in bad shape. It was the help of a free legal aid lawyer that saved the day.

OO: He sued the bank?

NO: Yes, he had to sue the bank over continuous interest charges and he had to seek free legal aid to get justice. That is the background story.

When I finished my law degree, I did an internship with Justice Development Peace Center in Ondo State. That introduced me to my early work in the development sector. It’s really been a great time since then; realizing that you can do some little thing to impact lives of people.

Before my law school, my task basically was advocacy – educating students on child rights. After law school, I went into private practice for a while and I realized everyone was profit oriented so even at my place of work then, clients wanted lawyers to use delay tactics because they were not ready for quick adjudication on cases by using various injunctions. I was uncomfortable with this because I felt this was not justice.

OO: When was Gavel founded?

NO: Officially, Gavel was founded in 2017, when the BudgIT fellowship started.

OO: So, you were involved in human rights activism before Gavel right?

NO: Before Gavel, I basically did things that had to do with championing rights of people especially against security agents – police brutality, standing for rights of people.

My experience with the police has been interesting. Sometimes you encounter verbal and physical assault from security agents who believe you cannot talk to your clients and then you go to the police station to secure release, only to meet resistance from security agents on duty at the police station. Most times we argue until you are lucky to get the attention of the DPO or DCO. After a while, I have learned to go see the DCO who calls the IPO to iron things out.

The rank and file’s relationship with the public is very bad; often times, the senior officers are more reasonable. They accord you the respect as a legal practitioner, while the rank and file will shame and abuse you, especially when you are not ready to part with cash.

OO: How many people have you been able to release from the prison?

NO: At Gavel, we’ve had to release a lot of people. So far so good, we have released 16 people from prison that we had to file cases for in court to get them out. Another massive one, although it is still ongoing, is the suit filed against Ministry of Justice’s Department of Public Prosecution, the Prison Service and Commissioner of Police for Oyo State. The issue is that we have 538 awaiting trial persons in a prison facility in Agodi, Oyo state.

The funniest thing is that all these people have not been charged to court so far. They are just there! Let me explain how the process works. One of them has been in the prison facility since 2010; that is 8 years. We have another individual since 2011. So we have a lot of cases like that without prosecution.

In the Nigerian justice system, what they do is once a person is arrested and taken to the police station, sometimes they get bail at the police station but oftentimes, they are taken to the magistrate court which is meant to prosecute simple offences. Once at the magistrate court, they get an order to remand them in prison pending when legal advice from the Ministry of Justice will be prepared for a charge against them.

The legal advice should ordinarily not be more than 28 days but you will see it going to several years so it is difficult to get them out. However, what should ordinarily take few days takes many years and that is where the bulk of the work is and disconnection lies. It not uncommon to see Ministry of Justice officials forgetting the case; they don’t even remember some individuals are behind bars waiting for prosecution.

OO: Are they supposed to put them behind bars and not police stations?

NO: Yes, the police officer takes them to magistrate court which then remands them in prison. However, the magistrate does not have the power to try all offences; they only have powers to preside over simple offences. But when they take cases of armed robbery, murder, defilement, and rape, the magistrate would rather remand them in prison.

OO: What is the next step?

NO: They are supposed to forward it to the Ministry of Justice, and charge them to the higher court. So once they forward the case file to the Ministry of Justice, they instruct the police to forward the case file to the Ministry of Justice. Where the bulk of the delay occurs is in the Ministry of Justice. Sometimes, they forget; even despite the intervention of a lawyer, it still takes six months to do the needful but if you don’t have a lawyer then you are doomed! You can just be forgotten there.

There is no synergy between major stakeholders’ agencies in the process of prosecution. The ministry does not interact with the police and likewise, the prison service. The quick and accelerated justice system has been made difficult because of that disconnect.

OO: What is Gavel doing about it?

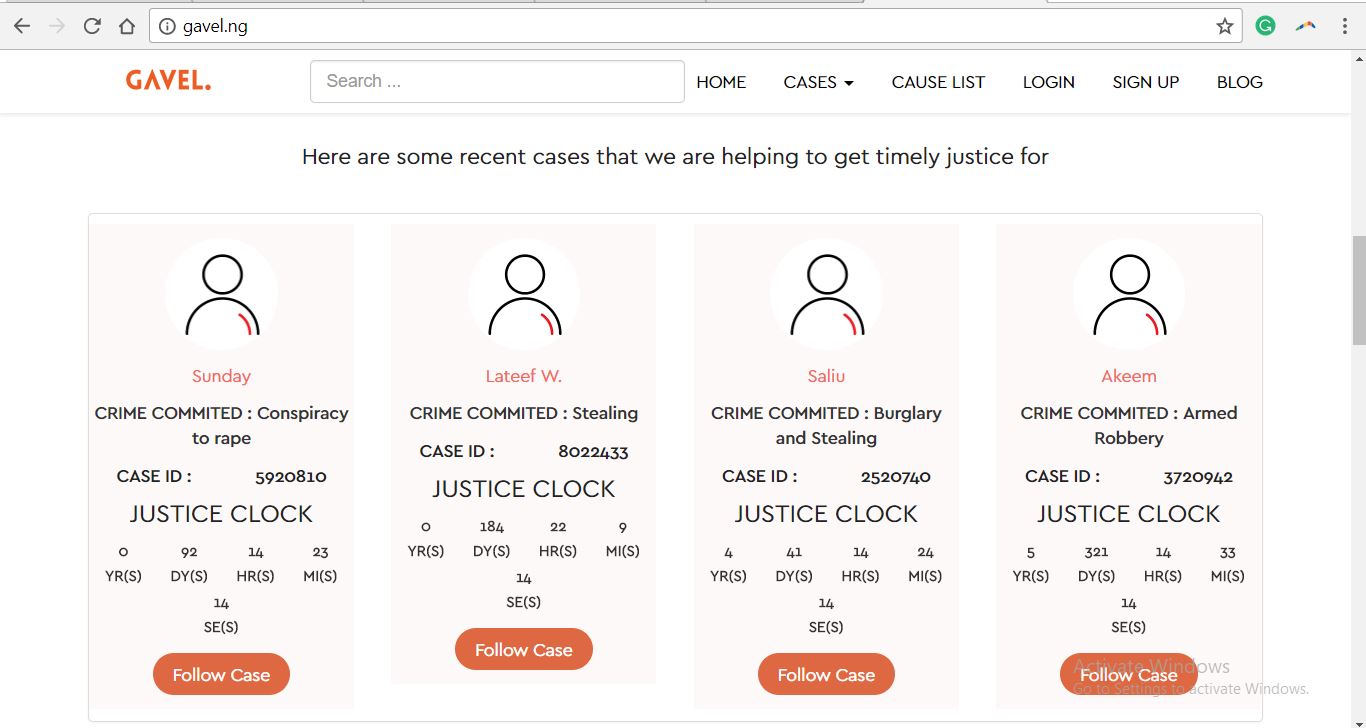

NO: What we do is track the cases of these awaiting trials using our justice clock tool. It is like a timer that keeps track of time being spent by an awaiting trial person behind bars. So we try to track their cases and see that the Ministry of Justice does the needful and charges them to court on time.

OO: Do you have a network of people that help out with all these cases?

NO: That is why we have the legal clock which is on our platform. We put some of the data there. It is an automated system so you know the number of days spent by an individual. We then compare the justice clock with the number days that should be spent so once they spend more than the days required by the law, we either file a case on their behalf, or we interact with the Ministry of Justice to see how we can proffer solutions and accelerate the pace at which their cases can be heard.

OO: So immediately you do that, the Ministry of Justice speeds up the trial?

NO: Sometimes they are not cooperative, which is why we had to institute a case against them in respect of those 538 awaiting trial persons. We expect to get a court order to compel them to charge them to court. So we are forcing them to do a job they are supposed to do. We expect to reconcile all the data and charge all these people to court.

OO: Does your own work finish there?

NO: No, we still go all out to represent them in court because some of these accused have lost contact with their families while in prison and nobody remembers them anymore. For example, we have an awaiting trial person who was accused of murdering someone while returning from his farm by a police officer because he was holding a cutlass; the police officer has been transferred while his wife has remarried and his mother only came once.

OO: There is a social stigma attached also?

NO: Yes, some of them have family members who just abandon them and some of their families cannot just afford coming to visit them. Sometimes, we have to fund the transport fares of their family members to court.

OO: Do you visit them in prison and interact with them?

NO: Yes, the conditions in those prisons are really deplorable but my visit to Kirikiri Prison showed that the condition was much better compared to others I have visited. The Agodi prison is really overcrowded and most of the inmates don’t even have space to sleep at night. Some of them don’t even take their baths.

Interaction with the inmates shows that there is so much suffering in the cells where inmates cannot sleep with their backs on the floor. Most of them come out with skin diseases and other infections as a result of the poor hygiene level in the prison.

OO: What kinds of offences are most common among the inmates?

NO: Minor offences. For example, one was accused of stealing goods worth N6,000, while another, who happens to be a caterer, was accused of stealing a pot and was remanded in custody when it became impossible to perfect her bail conditions.

OO: How do you fund their bail?

NO: Personally from our pockets and support from the fellowship. A person is granted bail with sureties, in the like of certain amounts, say N50,000. Meaning if the accused cannot be found then the surety will pay the amount.

OO: Have you had situations where some ran away?

NO: No, some even want them to clear their names. The police verify the details of the surety and pass the bail bond and even tax clearance for documentation. To do an average bail, you might be doing an average of N30,000 on each individual. For this, other lawyers take N70,000.

OO: How do you pick cases you want to handle?

NO: I have been working closely with the Prisons Service to give me cases and they know that I want to interview inmates with no lawyers. We take simple cases with little burden financially.

What we intend to do now is to provide a platform where people can access free legal aid lawyers online. Just come to the platform, create a case and we will help you out with free legal assistance.

We currently have 52 lawyers on our network and cases that we cannot handle in-house, we distribute to our network of lawyers. So we are looking at access to justice using tech to scale and anybody can access justice irrespective of location.

We are also looking at ways to use data to improve coordination in the justice system and also accelerate prosecution. We also have Court List, where we have a list of cases scheduled for hearings in courts weekly.

This gives us data on numbers of divorce cases, rape cases, and other cases; this will improve the justice system – using the data to analyze areas where there is a lag in the justice system value chain. We are also looking at integrating the legal clock into our justice system for judicial officers. So what we want to do is to facilitate speedy justice dispensation and also help with free legal aid for the poor.

OO: Do you still keep tabs on them after their release?

NO: Yes, they reach out and we work with their family members to aid their integration back into the society. We also have cases of underaged persons being kept in prison facilities. We also provide feeding for inmates.

OO: Thanks for your time

NO: You are welcome.

Additional reporting by Fikayo Owoeye