There is a raging debate ongoing in Nigeria about a minimum wage, with all parties appearing to have their ‘daggers’ drawn.

Both Labour and the Government acknowledge that wages need to increase, but the disagreement lies in by how much, how to implement the suggested changes, who will pay for it and who is responsible for paying for it.

This quagmire is setting up a finale that could affect the economy for years to come.

A country’s minimum wage is one of the most important economic metrics that underpin economic growth. For this reason, we will dedicate the next 10 minutes of your time to explain how Nigeria can resolve the minimum wage quagmire.

Nairametrics’ audience will be familiar with one key model economists use to measure the size of an economy, specifically that GDP = C + G + I + Nx.

In this formula:

- C refers to Consumption,

- G is Government Spending,

- I is Investments, and

- Nx is Net Exports.

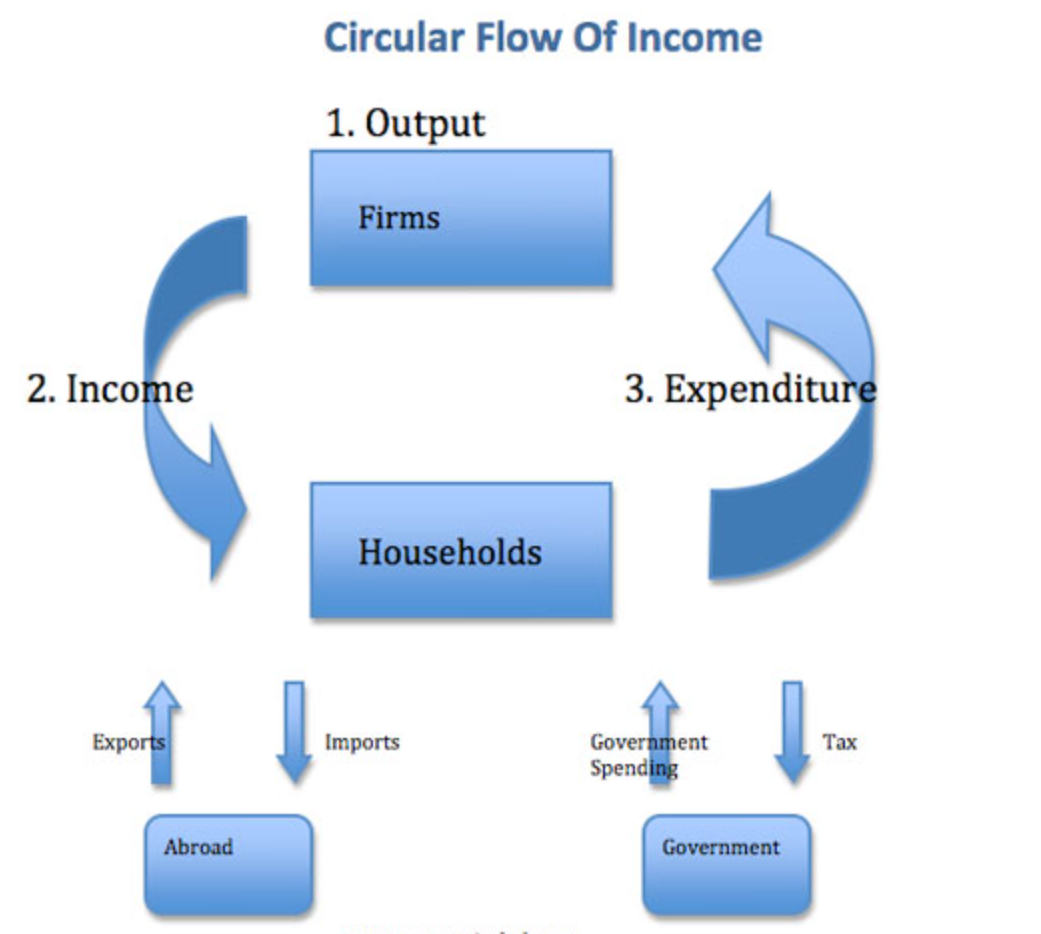

This GDP formula is supported by economists who advocate for the four-factor circular flow model of an economy. This model categorizes participants into four groups:

1. Households (Consumers)

2. Businesses (Investors/Producers)

3. Foreign Markets (Exporters)

4. Government

Understanding these components and their interactions is crucial for analyzing and fostering economic growth.

In its simplest form, this four-factor circular flow of income outlines that HOUSEHOLDS provide labour to FIRMS to produce goods and services, in return FIRMS compensate HOUESHOLDS with reward for labour.

HOUSEHOLDS, then spend the compensation on the goods and services. Consequently, FOREIGN MARKETS enable FIRMS import/export goods and services to optimize earnings and finally Government interjects to collect taxes and redistribute incomes through government spending

Thus, for an economy to grow, ALL the factors that make up the economy need to continue to grow and thrive TOGETHER and sequentially. That is, one factor cannot be ignored as everything is interdependent.

An example of interdependency, as HOUSEHOLDS purchasing power increases, they spend money on goods and services which enables FIRMS become more profitable and seek to expand that market. Furthermore, as FIRMS become more profitable, GOVERNMENTS will see more taxes and seek to increase expenditure targets.

Conversely, lower HOUSEHOLD earnings results in FIRMS struggling to survive and seek to exit the market resulting in lower taxes for GOVERNMENTS who either borrow more to fund initiatives or increasingly ignore their responsibilities to citizens.

No prizes for guessing which spectrum Nigeria is experiencing. Folks looking to learn more about the Four Factor Circular Flow of Income can read more here and here.

Why the preamble?

For many years now, discussions of how to fix the ailing Nigerian economy have focused ad infinitum on the other factors of the four-factor circular flow. Specifically

- how to better allocate government spending [which is G].

- how to attract investments into the country [which is I]

- how to grow net exports [which is Nx]

However, when debating how to rapidly expand the Nigerian economy the fourth-factor issue of how to turbocharge our domestic consumption and boost household aggregate demand is often overlooked.

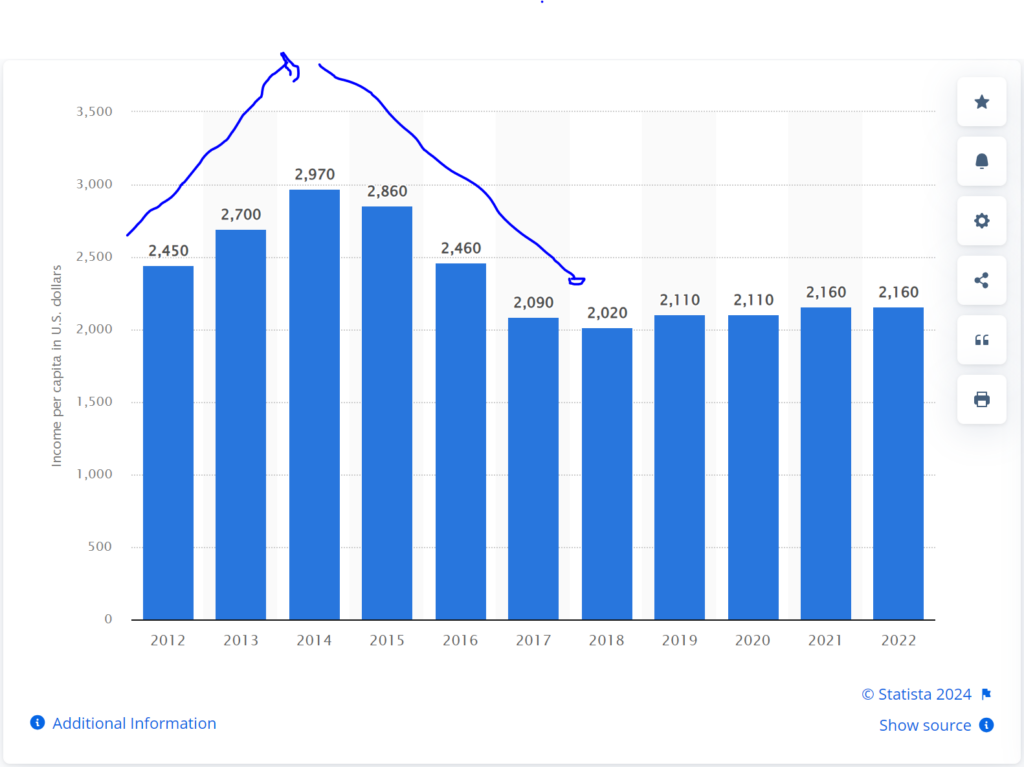

By international standards, we can argue that Nigerians are grossly underpaid for the work they do. For example, a driver is expected to report 7 am to 7 pm for ~N45,000 to N50,000 monthly (N1,500 per day).

In the corporate sector, junior staff can expect to earn between N100,000 to N150,000 monthly (N5,000 per day). Whilst the Federal minimum wage which was set in 2019 remains at N30,000 monthly (N1,000 per day).

Remarkably, these numbers compare to the World Bank’s International Poverty Line of $2.15 per day (N3,000 daily).

In other words, the vast majority of Nigerians earn below the recognized poverty level, and even entry-level staff barely earn above the poverty line (i.e., when they can get a job).

For a country looking to supercharge its economy, the issue of gross undercompensation of households means that our aggregate demand is neither going to sustain nor drive economic growth.

What this means

If Households continuously fail to demand for goods and services due to declining purchasing power, this will mean that Firms will rapidly become unable to pass cost adjustments to consumers resulting in Firms becoming unprofitable and look to depart.

- The adverse impact on Government is clearly loss of taxes (both corporate and personal etc). From a Nigerian perspective, household earnings have been declining for over 10 years.

However, rather than fostering discussions on how to reverse this declining trend and turbocharge Nigeria’s household earnings, we saw an explosion of government direct interventions in the economy via increased subsidies and development finance funding.

- Unfortunately, government direct interventions in an open economy creates market distortions and is NOT an adequate substitute to replace declining Household demand.

The last decade has shown that Direct Government Intervention funds can easily be misused or misallocated with adverse consequences.

The best transmission mechanism for economic prosperity in any economy remains a thriving capital market supporting companies to grow, employ workers and reward productive employees via compensation. But this is a topic for another day.

So what is happening now?

The present administration has suggested it wants to scale back direct interventions and subsidies. This includes eliminating subsidies on fuel, electricity, foreign exchange amongst others.

This policy stance was interpreted to mean that the present administration was keen on adopting a more orthodox approach to managing the economy.

- If it is truly the case that the present administration is trying to adopt an orthodox approach then the government cannot pay lip service this time to household earnings.

Specifically, the elimination of subsidies and the misallocation of intervention funds are leading to an unsustainably higher cost of living for everyone, with no immediate benefits for businesses and individuals, prompting a mass exodus from the country.

We have already witnessed the ‘Japa’ phenomenon among our youth from 2019 to 2023. This trend is now escalating to ‘Japa 2.0,’ as recent news articles highlight companies exiting the country, indicating that businesses are rapidly following individuals out due to mounting losses and cost pressures.

The ongoing debate about raising the minimum wage is certainly welcome and long overdue. However, the focus of these discussions is alarmingly inadequate.

- Rather than fixating on arbitrary figures like N62,000 or N100,000 per month, the conversation should center on creating a framework that enables Nigerian households to maximize their earning potential.

Turbo charging Nigerian HouseHold income

As previously mentioned, given that the present administration is keen on eliminating subsidies as part of a return to orthodox economic policies, this approach needs to be applied comprehensively across all economic factors, including household earnings. In other words, if there is a need to allow previously subsidized products such as fuel, electricity, and foreign exchange to reflect market prices, then household earnings should also reflect market conditions.

The ongoing conversations about the minimum wage suggest a wide range, from N62,000 to N250,000. This raises the crucial question: what should the market rate be? Here are a few broad-brush approaches that can be considered:

Approach 1: Use the World Bank International Poverty Level rate as a benchmark, which is $65 per month or approximately N95,000.

Approach 2: Take the minimum wage set in 2019 and adjust for the average monthly inflation rate of 1.6% over five years from June 2019 to May 2024, resulting in a figure of approximately N77,758 (based on N30,000 adjusted by an average monthly inflation rate of 1.6% compounded over 60 months).

Approach 3: Set a rate comparable to peer African nations. For instance, Morocco has a minimum wage of $285 per month and South Africa $250 per month, giving a range of approximately N375,000.

Regardless of the approach taken, it is clear that the appropriate figure is neither N30,000 nor N62,000.

To be clear, advocating for an increase in minimum monthly compensation from N30,000 to N250,000 or even market driven compensation of N375,000 let alone N500,000 does not acknowledge the fact that the Federal Government has been running fiscal deficits for over a decade with the fiscal deficits getting worse each year.

However, the economic principle remains that if the government wishes to eliminate subsidies and direct interventions, then household earnings need to increase, starting with setting a more market-driven minimum compensation.

Otherwise, aggregate demand in Nigeria will collapse, adversely impacting firms and, in turn, the government through reduced tax receipts and increased borrowing.

- The dilemma is that as the government seeks to eliminate subsidies, Nigerian household earnings must increase. However, a one-time rapid adjustment of compensation to market-driven rates creates an affordability challenge for all employers of labor.

If there is an acknowledgment that household earnings must increase as part of a return to orthodox economic policies, then a potential way to address the affordability quagmire is to link compensation directly to increased revenue productivity.

One idea being floated is to set minimum compensation on an hourly basis. This approach must include allowing workers the flexibility to provide services to multiple employers.

The focus should be on ensuring that workers can earn above poverty levels, even if it means being employed by two institutions.

- In this scenario, setting a minimum hourly compensation rate means that employment contracts cannot restrict individuals to working for a single employer.

- Additionally, working hours will need to be more flexible. For example, an employee could work from 8 am to 1 pm with one employer and then from 2 pm to 6 pm for another.

- This arrangement translates to nine hours of work daily and generates monthly earnings of over N106,000 using a minimum compensation of N570 per hour. This way, the working hours are spread across two companies, thus not overburdening a single employer.

An alternative to the hourly rate is to create a structure where workers have a base pay but can earn significantly more if their performance warrants it. This base plus performance pay model can be applied on a monthly or annual basis.

- For example, a minimum wage of N95,000 could comprise of a base pay of N62,000 coupled with a N33,000 performance bonus for reaching realistic IGR targets or output

- This base pay plus performance approach has precedents in other countries.

- The key here is that enabling households to earn more as revenue productivity improves means that everyone wins. Workers are incentivized to attract firms to their region, fostering business growth.

- As firms grow and generate more revenue, they hire more employees, which ultimately leads to increased government revenue from corporate income tax (CIT) and personal income tax (PIT).

A third alternative is to set a minimum compensation indexed to inflation, ensuring household earnings increase yearly.

- For example, a minimum wage of N62,000 with a 30% annual inflation adjustment would rise to N80,000 the following year, although this is still below World Bank International Poverty standards.

- This alternative could serve as an incentive for the government to be more accountable and to avoid policies that cause rising inflation and a higher cost of living.

In conclusion, as the debate over a new minimum wage continues, it is crucial for all parties to understand that this discussion should not be limited to simply setting an arbitrary number as a one-time exercise that remains stagnant for another twenty years, pushing the nation backward in real terms.

Instead, the focus should be on recognizing that household earnings are a critical part of the income flow in an economy and need to continually increase as productivity rises.

As a nation, some urgent questions include:

- How quickly can we restore increased disposable income so that our businesses can adjust prices and become profitable again?

- How quickly can businesses achieve profitability through elevated aggregate demand, thereby attracting more investment to the country?

- How quickly can internally generated revenue (IGR) linked to taxes increase without being a burden on profitability?

None of these questions can be answered without addressing the decimated aggregate demand in the economy caused by weakened household earnings.