Nigeria took her first foreign loan in 1964 for about $13 million to finance the construction of the Kainji dam. Today, the nation is locked in a debt crisis as she reportedly spent 97% of her revenues in 2020 on debt servicing.

In 2020, Nigeria’s Federal Government (FG) collected N3.42 trillion as revenues and spent N3.34 trillion to service her obligations. In effect, every other expenditure of the FG was done via borrowings.

I want to take a deep dive into Nigeria’s debt picture; what happened? Was it an omission or policy? How can debt grow to the level it has in so short a period?

The Background, 2004

Total debt: $46.25 billion

Total External: 63%

Total Service: $3.28m

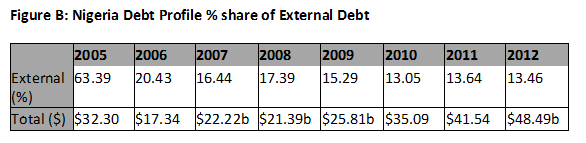

2004 is the earliest record we can get from the Debt Management Office of the Federation (DMO). From 2001 to 2004, 63% of Nigeria’s debt was external and owed to the Paris Club of creditors (see Figure A). The total debt profile for Nigeria as of December 2004 was $46.25 billion. According to the DMO report, “The bulk of these loans were due to accumulation of arrears, penalty charges, and exchange rate movement rather than new borrowings.”

I wrote last year about Nigeria’s debt buyback program. The former Minister of Finance, Ngozi Okonjo Iweala was quoted as saying, “The rescheduled amount in December 2000 comprised 24% late interest; 21% interest; 48% principal arrears, and only 7% principal balance. The external debt as rescheduled was made up only of 7% of the principal sum, the rest were penalties, and these penalties had accumulated to the tune of about $5 billion.”

The milestone years

2005

Total debt: $32.30 billion

Total Service: $10.10 billion

Total External: 63.39%

In 2005, Nigeria signed the Paris Club debt deal, which offered Nigeria the opportunity to get substantial debt relief and led to the external debt drop by 43%. Domestic debt increased by 14% in 2005 from the preceding year. 2005 was a good year for Nigeria as she reduced her expensive external debt. In 2006, Nigeria’s total debt was about $17.34 billion, a 46.30% drop from 2005. Foreign debt now made up about 20% of the total debt see Figure 2.

Foreign debt in 2006 was just $3.54 billion, and debt service had dropped to $8.04 billion, a 20% drop from 2005. This drop was because Nigeria exited the Paris club obligations. However, domestic debt went up as the government turned to the domestic market to replace the foreign borrowings. In 2006, domestic debt overtook foreign debt. 2006 can be called the golden year of debt management in Nigeria as the expensive foreign debt was all but gone.

2009; Nigeria transits to domestic & non-concessionary borrowing

Total debt $25.81 billion

Debt Service: $2.33 billion (decrease of 42.41% from 2008)

Total External $3.94 billion (15.29% of total debt)

In 2009, the foreign debt went up slightly by 1.81%. The domestic debt climbed to $21.87 million, constituting 84% of Nigeria’s total debt. The debt services fell 42% because the FG refinanced its bonds. External debt strategy also shifted from accessing non-concessional to concessional loans as well. Concessionary means the loan has a minimum grant element of 35%—however, it’s critical to note that the bulk of the debt servicing went 81% to local debt.

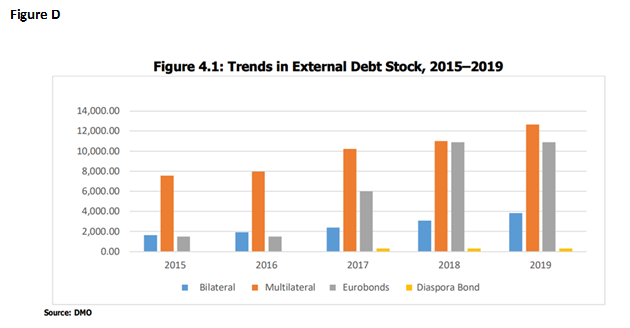

In 2010, the foreign debt went up slightly. While the external debt service payments continued to fall, the domestic debt service went up. The FG was using domestic bonds to fund its budget hence the increased servicing costs. There was an increase in non-concessional loans in 2011 because $500 million Eurobonds were issued for the first time. Both external and Local debt went up.

In 2012, Nigerian bonds were added to the JP Morgan Global Bond Index Emerging Markets Local Currency Bond Index (EM-LCBI). Non Concessionary loans (Commerical loans) rose to 19.30% from 12.31% in 2011. The total share of debt service for external loans was 5.96%, while domestic was 94.04%. Debt Service for 2012 was $4.91 billion, an increase of 30.09% from 2009, and about 2.04% of GDP.

In 2013, Nigeria was classified as a Lower Middle-Income country due to growth in Nigeria’s per Capital from $1496 in 2011 to $1565 in 2012. The implication of this elevation of Nigeria to a “blend” country status was that Nigeria lost access to most concessional sources of finance.

The decision years; Nigeria goes foreign

2016

Total debt $57.39 billion

Debt Service: $4.38 billion

Total Foreign Debt: $11.40 billion

By 2016, Nigeria’s foreign debt had ballooned to $57 billion, past the 2004 number negotiated with the Paris club. However, the bulk of these loans were still local, with foreign debt at 20% of the total debt (See figure C).

The Federal Executive Council approved a new Debt Management Strategy 2016-2019 on June 15th, 2016. It specified “substituting the relatively more expensive domestic debt with less expensive external debt from both Concessional and Non Concessional windows.” Thus in the future, there would be a shift in focus to external borrowing. Debt service fell due to a decline in FGN domestic debt stock; however, debt service on external debt increased to $353 million from $331 million.

This decision to replace domestic debt with “cheaper” foreign debt was, in my view, the catalyst of the debt crises Nigeria now faces. Foreign debt may be more affordable rate-wise, but what about Exchange Risk? Essentially Nigeria was betting that Exchange Rates would remain strong to pay off her USD denominated debt. Debt service was still $4.3 billion.

By 2020, Nigeria’s debt profile has changed; Nigeria now owed more to foreign creditors than local creditors. Total debt at approximately $86 billion with foreign debt at $33.34 billion, making up 37% of the total debt. Debt Service had shot up to $6.16 billion.

The issue is that Nigeria borrows in foreign currency, with a significant portion of those foreign currency loans being commercial Eurobonds. See figure D. What are these Eurobonds being used for? according to the DMO, 40.35% in 2019 is deployed to “budget support.” (See figure E).

Nigeria today has a higher debt profile than in 2004, and foreign creditors again held the Nigerian debt. Just as in 2004 when Nigeria had crude oil as the only source of foreign exchange, in 2020, Nigeria also has just crude oil to pay down her foreign loans.

While the Federal Government can access CBN Ways and Means to meet Naira’s obligation to the tune of N275 billion in Q1 2020, it can’t print USD; it has to earn them. The Covid-19 pandemic caused oil production to stall, and Nigeria’s crude oil receipts as of Q1 2021 are negative 69% from the target. What happens if oil pieces fall? How does Nigeria pay?

Solutions

The policy of substituting domestic debt with external debt has failed to reduce the debt servicing cost, and it should be reviewed.

Nigeria should go back to accessing only non-concessionary loans for revenue-generating projects and continue to seek concessionary loans for budget support activities.

Nigeria has a spending problem. Spending and waste have to be cut.

Poor write up.

Nice idea, good statistics, poorly written article.

You might also wish to include

1. a broader Figure E (table 4.6) to cover the past 25yrs (1996-2020) at least, including as much of 2021 as possible.

2. the heads of state/presidents in office as at the time of taking those debts (during each of those years) for more insightful information.

3. the CBN Governor in charge during those years