“Giving subsidies is a two-edged sword. Once you give it, it’s very hard to take away subsidies. There’s a political cost to taking away subsidies” Najib Razak, current Prime Minister of Malaysia

Nigeria’s struggle to price gasoline appropriately is almost like most other government controlled things – its currency, electricity, natural gas etc. never gets it right. It is worse with gasoline which it ironically has the ability to control due largely to the fact that it produces nearly 2 million barrels per day (bpd) of crude oil and at some point possessed 445,000 bpd of crude oil refining capacity despite only consuming about 300,000 bpd of the product.

The country is dependent on fuel imports for its gasoline needs and has to subsidize to prevent prices from rising too high. Thus, while shipping tonnes of crude to the global oil market daily, it faces recurring problems with fuel scarcity; disputes between fuel marketers and the government. The government is saddled with a burden for fuel subsidies that keeps rising each year. Despite a nearly 50% reduction in government revenues in 2015, the country forked out about N1 trillion naira on fuel subsidies to end a recurrent fuel scarcity in the country. But subsidies are only half the problem. The low price of gasoline in Nigeria has created a significant arbitrage opportunity for gasoline between the country and its neighbors’. Consequently, a lot of gasoline is smuggled over the borders into neighbouring countries, even while the smugglers claim subsidy on it. As at mid-December 2015, the arbitrage between gasoline prices in Nigeria and its neighbors’, was averaging nearly N75 a litre.

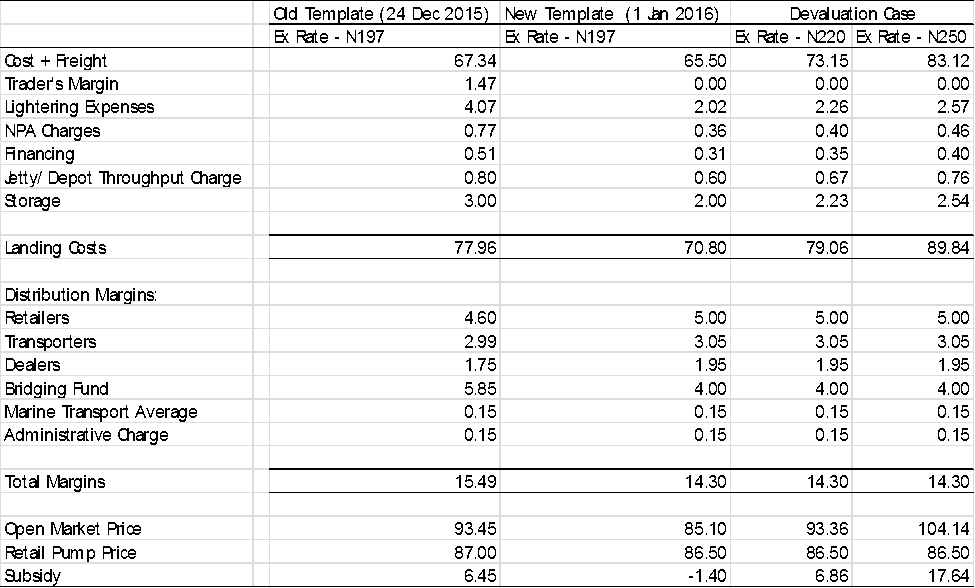

Pricing Template

The country’s gasoline is priced by an agency of the petroleum ministry called the Petroleum Products Pricing & Regulatory Agency (PPPRA), which was established in 2003. The PPPRA developed a pricing template in 2007, which has remained unchanged till recently (December 2015). The template is divided into two broad segments, the first is the composition of the landing cost of gasoline and the second being the margins for distribution of the product. The two sections together make up the open market price of gasoline or the full price, which is typically higher than the official pump price; the difference being the fuel subsidy.

Issues with the template

There have been several complaints about the pricing template of the PPPRA. The first being the fact that it uses the higher grade NWE Platts gasoline bought by European buyers while Nigeria imports a lower grade gasoline with a higher Sulphur content. This grade is at least $25 – 35 cheaper per tonne than the reference grade. However, Platts has only begun in 2015 to publish an assessment for the West African gasoline grade. The template is also static with its charges and margins remaining unchanged since 2007 when it was developed. Consequently, even if the actual charges and margins have fluctuated over the years, the cost-savings have not been passed on to the final consumer. The reverse has been equally true. More importantly, the static margins have made the petroleum marketing business, a low-margin business, saddled it with a lot of debt and only appear profitable on the long term for companies with investments in other segments of the oil and gas value chain. The final complaint is often the fact that there are several other smaller fees, duties and charges faced by marketers not captured in the template. Although these are supposed to be covered in bridging cost, they are not typically recognized for payment, i.e. additional security costs in distributing to troubled parts of the country, passage fees paid to street urchins in some suburbs of major towns, union fees and various bribes collected at depot/refinery gates to enable trucks load gasoline.

Changes in the template

The recent changes made in the template were however targeted at only resolving one issue – reducing the government’s subsidy burden by ensuring the full price was at a level where it no longer needed to pay anything. This was achieved by slashing the NPA, jetty throughput and storage charges included in the landing cost and the bridging fund fee included in the margins for distributors of gasoline. This changes enable the PPPRA reduce the open market price of gasoline to N85 per litre from N93.45 previously. The new template is to be assessed quarterly and only on an adhoc basis if the PPPRA senses there has been a substantial development warranting an assessment. This is expected to make sure the template is more reflective of market condition unlike the previous static template. Notably, margins for retailers, transporters and dealers are slightly higher in the new template than previous templates, giving them some confidence in the new plan. More importantly, the template achieves the government aim of having no more subsidies to pay as the open market price of N85/litre for Q1 2016 is less than the pump price of N86.50 yet this pump price represents a reduction on the previous N87/litre.

Source: PPPRA, analyst calculations

Risky template

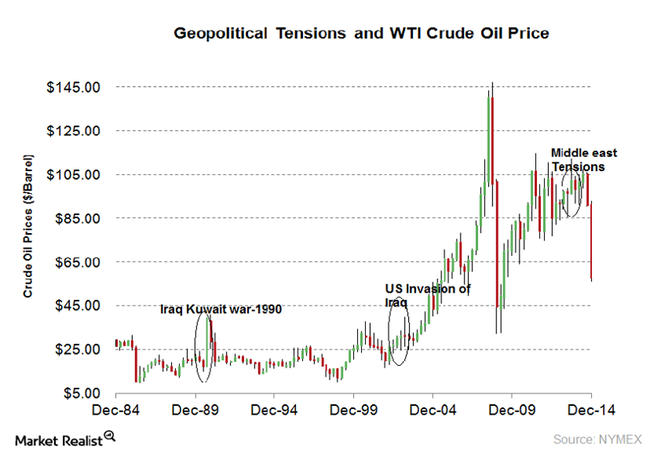

However, there are real risks to this happy picture. The two key risks are potential devaluation by the CBN and the risk of geopolitical crisis leading to higher oil prices. According to most analysts, the CBN could succumb to growing pressure to devalue the naira by allowing it float within a wider band; some have suggested between N199 and N220 per dollar, while others suggest to as far as N250. At N220 per dollar, the gasoline price shoots up to N93.86 at current landing costs, while it rises further to N105.30 if the naira is devalued to N250. If oil prices also increase and rise above $40, there’s a possibility the landing cost for gasoline could also rise above the current N71/litre. Although this is more far-fetched than a devaluation prospect, oil rising to $45/bbl. could force a major upward increase in the open market price to around N91/92 per litre as well, at current refining margins. Geopolitics has always played a role in resetting the global oil market during periods of prolonged lower oil prices such as we have currently. Thus, it is possible that if the oil price remains low, it could spark unrest and unrest in major oil-producing countries as their governments cut key benefits to the people to manage their fiscal pressures, creating supply shocks.

If any of the two above scenarios occurs, the Petroleum Ministry and the Federal Government would thus have to take a decision to either announce higher gasoline prices or re-introduce subsidies for a short period. The expectation would be that higher oil prices could potentially strengthen the Naira and reverse some of the potential effect of higher oil prices on landing costs. However, the naira’s ability to strengthen during periods of higher oil prices has been historically haphazard. Furthermore, if the CBN chooses to devalue, and the cost of imports increases, this could be countered if the 3 functional refineries are able to produce at about 60% capacity. This would represent about 78% of the country’s consumption, reducing the need for imports. However, there is no guarantee that the refineries will be able to achieve this feat due to feedstock supply and pipeline/offtake security issues.

Best Solution

In my opinion, these issues make the NNPC’s revamping of the pricing template at best, a short term solution. The country needs to liberalize its gasoline market but this has to be achieved gradually to avoid some major issues. The lack of infrastructure to distribute the product across the country would suggest a move towards differentiated pricing, as against the current uniform price, such as is obtainable in Kenya where the prices are graduated based on distance from the major port of entry in Mombasa. Furthermore, due to the importance of gasoline (65% of fuel consumption in the country), full liberalization of the market and potential collusion among major marketers could send prices high in many parts of the country and keep them high. Thus, the NNPC retail arm must remain a key player in the market.

In my opinion, it needs to be the largest player in the market with distribution capacity in all parts of the country, giving it ability to influence prices without government having to set prices for everyone. To achieve this, it may require corporate finance support from the capital market, even if not listed. Ultimately deregulating the market will allow private investment into smaller modular refineries, augmenting the huge investment by Dangote, which could eventually focus more on export markets considering Sub Saharan Africa’s huge fuel imports.