Managers of successful economies fear nothing more than inflation, for them even if incomes don’t increase prices must at least stay constant (or within the desired level). In Nigeria, inflation runs on average of 12% per annum for 10 years now and it is seen as normal.

SME owners often bear the brunt of high inflation because of their inability to sustain operations when prices of energy and raw materials are beyond reach, turning prior investments in fixed assets into sunk costs. Civil servants are next in line due to the nature of their wages which in Nigeria is sticky upwards, as it is easy for them to go months without pay.

Regrettably, the political economy of civil servants agitations for wage increase creates an inflation spiral because the government make it a fanfare for political correctness. The corollary effect of this is that all prices automatically adjust upwards that is why experts agree that inflation is not just the purview of economics but equally of psychology. This article will try to dissect the pestering issue of high inflation and to educate us on its causes with the aid of data (as usual).

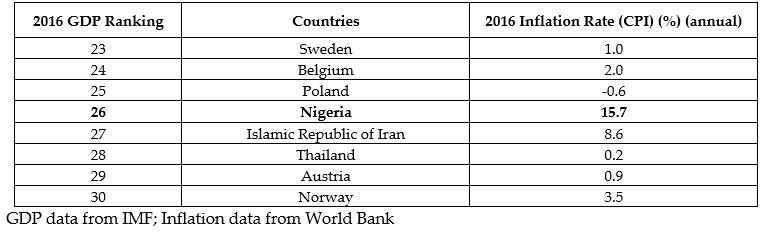

Let’s begin by showing a list of countries by GDP ranking and their inflation rate. From the table below, one can see that from all the countries about the size of Nigeria’s economy, only Nigeria has the scariest inflation rate. Even oil-rich Iran that swims in petrodollar has two times less Nigeria’s inflation rate.

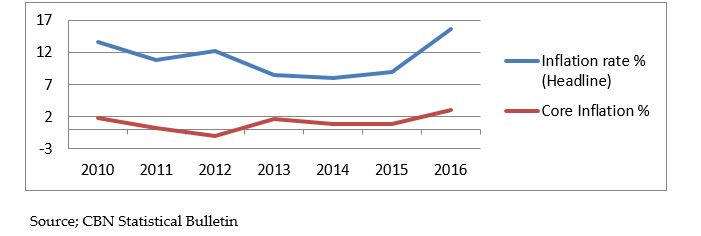

The figure shows inflation rate averaged 12.09% from 2001-2016. This means that within 16 years prices have skyrocketed by 193%. There can only be one reason for this type of sustained inflation, a failure of monetary policy. There is a popular opinion that core inflation (food & energy prices) drives headline inflation (all items) as seen in countries with a significant manufacturing sector.

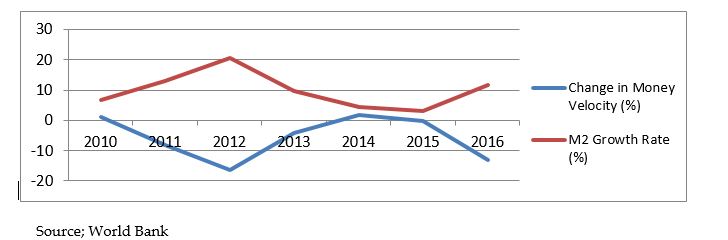

The above data does not tell the whole story from years 2013-2016. This could be because of major Naira devaluations (in the black market) of those years in what is called exchange rate, pass through mechanism, given Nigeria’s heavy dependence on imported fuels. We move on to check how many times a Naira exchanges hands in the economy in what is called money velocity. Experts believe that money velocity should be constant that is money needed for transactions should just be enough to match the level of economic activity at any particular time especially in an environment of low technological innovation. As we shall see if the CBN alters its currency prints (or electronic money), the velocity of money will be unstable.

We can see above that the inverse relationship between money velocity and money growth rate (M2) is upheld, whereby, when M2 had its most expansion in 2012 at 20.60%, a flush of Naira exchange hands at 16.3% times less. Also when M2 contracted the most in 2015, change in money velocity was close to zero (quantity of money almost matching transaction level).

So what causes large swings in M2? To answer this, we have to agree that money is created in two ways; one by commercial banks through deposit creation, although in terms of composition (in absolute terms) it is the largest but this method is slow and still dependent on its high powered counterpart domiciled in the liability side of the CBN balance sheet. This brings us to our culprit of M2 growth; currency in circulation and in commercial banks vaults (reserves).

Proactive central banks know better not to print excess worthless paper (currency), but, in the case of Nigeria, a few (cogent) reasons will suffice. Firstly CBN monetises crude oil sales (prints Naira for Dollars) and shares to different tiers of government but tries to subdued this effect by mopping up the excess currency through $200Million fortnight sale (about N72 Billion) and a further N300 Billion quarterly auction of treasury bills.

Money is a flow concept and its measurement ambiguity creates problems for an exact comparative analysis such as this. Notwithstanding, there is another major source of money creation or printing the CBN engages in which especially has to do with its leadership answering to the whims and caprices of political leadership.

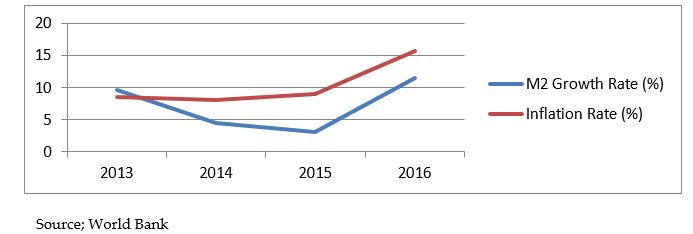

In other words, it is the printing of money (by anyways & means) for the Federal Government to spend. This type of money creation cannot really be factored into CBN’s monetary management because it is largely unplanned unlike debt instruments and has the tendency to cause dislocations in the economy, especially in the overall price level. The chart below answers our query that indeed excess currency in circulation causes sustained inflation in Nigeria by the close movement of M2 growth and inflation rate.

Prior to 1990, New Zealand had the highest inflation rate among developed countries. This made them reform their central bank and instituted a long-term inflation target of 0-2%. Part of their central bank law allows for the sack of the bank’s governor once the target is not met, though, that law has never been used because of the bank’s effectiveness.

New Zealand has one of the best anti-inflation mechanisms in the world. Same for the Bank of England Governor who must write to explain to the finance minister (exchequer) for every basis point increase in inflation. For long the CBN has not put forward an explicit inflation targeting regime. It seems to be more concerned with exchange rate and interest rate targeting. Aside a clear inflation target, experts the world over agree that central bank’s credibility is the best tool against inflation.

If a central bank commits itself to a goal or target and does every good thing in the book to actualise it, the corollary is that its independence will also be secured because politicians will cease to be overbearing believing it knows what it’s doing. But can we say this is the way of Nigeria’s central bank?

Can you explain how it will affect the daily lives of the citizens?

There is a lot I do not understand from this post.