Nigeria, with its population of over 200 million people, has long operated on a cash-and-carry economic model.

You want to buy a car? Pay cash. A new home? Cash. Rent office space, go on holiday with family, or pay school fees? It’s cash, cash, and more cash.

Virtually all major consumer spending is done upfront, with little recourse to financing or credit.

In a country where informal commerce dominates and financial inclusion remains patchy, the culture of upfront payment is deeply entrenched.

It’s a way of life. A financially exhausting one.

Compare that to most of the modern world, where credit isn’t just a financial tool, it’s oxygen.

In the United States, credit cards, student loans, mortgages, and buy-now-pay-later are part of daily life. In the UK, you can get a loan to buy a house, a car, or even pay for a wedding.

In India, home loans and personal credit are increasingly common among its rising middle class. China’s consumer and business credit systems are massive, underpinning its property and investment-driven economy.

Even in South Africa, many consumers have access to credit cards, vehicle finance, and personal loans that make life more flexible, even if not always easier.

In those economies, credit is a lubricant, keeping the wheels of commerce and daily life turning. In Nigeria, by contrast, the wheels squeak loudly.

Yet something seems to be changing…albeit slowly.

Credit fever in the age of cashlessness

The Tinubu administration’s tough-love economic reforms, fuel subsidy removal, exchange rate unification, and electricity tariff adjustments have made life more expensive for virtually everyone.

Nigerians have watched their purchasing power collapse under galloping inflation, much of it triggered by recent economic policies. Savings have lost their value, no longer able to fund future expenses. It’s unsustainable. For many Nigerians, consumer credit is now the only feasible way to maintain or improve their quality of life.

And so, out of necessity, not design, consumer credit is finally having its moment.

And the administration seems to have caught the bug.

First came CrediCorp, Nigeria’s Consumer Credit Corporation, launched in 2024. Its mandate? To create and extend credit to workers and small businesses. So far, about N3.5 billion has been disbursed. Not mind-blowing, but better than zero.

Meanwhile, the Renewed Hope Housing Programme, the administration’s flagship housing initiative, claims to have disbursed N59.3 billion via the Federal Mortgage Bank, with another N46.9 billion allocated to new housing developments under the Renewed Hope City project. Nigerians may one day buy homes without needing to drop N120 million upfront for 50% based on off-plan instalments.

And then there’s NELFUND, the student loan fund birthed from the revamped Student Loan Act. As of April 2025, it had disbursed over N54 billion to more than 290,000 students. This could be a game-changer, ensuring access to higher education doesn’t depend on whether your parents can raid their savings or sell land.

Then came the big announcement: the launch of the National Credit Guarantee Company (NCGC) with N100 billion in initial capital.

The idea here is clever if Nigerians can’t get credit because lenders are scared of defaults, let the government step in and share the risk. NCGC’s role is to guarantee loans so banks, fintechs, and co-ops feel safer extending credit to ordinary people. Risk-sharing 101.

Altogether, these institutions are painting a picture, albeit still rough, of a future Nigeria powered by credit, not just cash.

But the picture is not yet complete

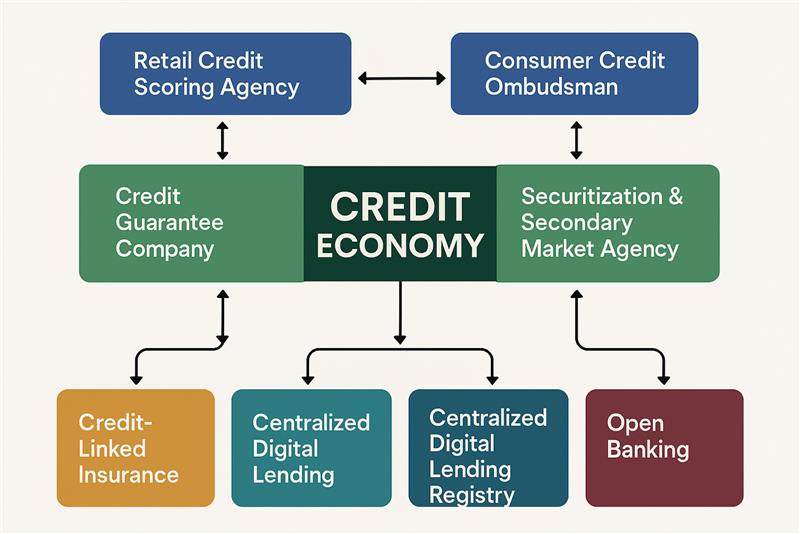

While the canvas is taking shape, several brushstrokes are missing. For Nigeria to unlock a truly dynamic credit economy, the government needs to go further.

First, Nigeria needs a retail credit rating agency, separate from credit bureaus. Existing entities like CRC and Credit Registry provide reports but do not offer risk-based scoring that lenders can rely on for pricing loans. A dedicated retail credit agency would enable more accurate risk profiling and reduce interest rate distortions.

Second, a Consumer Credit Ombudsman or Financial Protection Bureau is critical or standalone Financial Protection Bureau.

Because let’s be honest: when credit goes sideways and it often does, there needs to be a credible, independent channel for dispute resolution.

In the U.S. and UK, such institutions have helped protect borrowers and increase trust in credit systems. In Nigeria, consumer complaints often bounce between banks, the FCCPC, and the CBN, with few getting real recourse.

Next, the country needs a Securitization and Secondary Market Agency. One major reason banks hesitate to lend aggressively is liquidity constraints. If consumer loan portfolios could be securitized and sold in a secondary market, as is done in the U.S. with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, banks could recycle their capital and expand credit further.

In addition, there’s a need for a credit-linked insurance framework. Currently, there is no structured credit life or unemployment insurance tied to consumer loans. Right now, if you lose your job, you still owe the loan, and the lender still takes the hit.

This leaves both lenders and borrowers exposed to shocks like job losses, illness, or death. A well-regulated insurance layer would encourage broader credit expansion.

Furthermore, a centralized digital lending registry is essential. Right now, lenders operate in silos. A borrower could take loans from four different lending apps or banks, and no one would know until it’s time to default on all of them.

There is some progress. Nigeria has the Global Standing Instruction (GSI), which allows lenders to automatically debit a borrower’s account in case of default. But it’s not automatic in practice.

Lenders still face multiple layers of approval, delays, and often legal bottlenecks before recovery is possible. So while the framework exists, it doesn’t offer real-time visibility or enforcement.

A centralized lending registry linked to all banks, fintech’s, and microfinance lenders would allow everyone to see who owes what, to whom, and when. It would prevent over-lending and help price risk more appropriately. Open Banking, expected to launch fully in August 2025, is a step in the right direction, but it needs to be supported by stronger regulation, adoption incentives, and real-time credit exposure monitoring.

So, how big is the opportunity?

In India, household credit to GDP is around 43%. In South Africa, it’s 36%. In Nigeria? A humbling 6%. If we were to simply catch up with South Africa, we’d be talking about a N60 trillion credit market. That’s an enormous pool of liquidity to fuel consumption, education, housing, and entrepreneurship.

For once, the economic hole we’re in might have a ladder, and it’s called consumer credit.

But let’s not romanticize it just yet. A country that’s spent decades surviving on cash and improvisation won’t become a consumer credit paradise overnight.

What’s required is a disciplined, intentional, and transparent approach. Credit can’t thrive in an environment of weak contract enforcement, poor identity systems, or erratic macroeconomic policy.

That said, it’s exciting to finally see the scaffolding go up.

In Nigeria, the cash-and-carry economy may not be dead yet, but it’s coughing. If we play our cards right, we could usher in a credit economy that allows more Nigerians to live now and pay later, not just because they have to, but because they can.

Very good analysis.

Just to add that the credit card project owes its potential to the existence of an active identity management system.

Without the ID system, there is no credit system.

This is the case in all countries with a working credit system.

So this needs to be captured in the story.

Nigeria grew its ID system from under 7 million users in 2017 to over 100 million by 2022.

The credit system was identified as one of the potential benefits.