The federal government’s subsidy reforms, rather than the expansion of money supply, are a major driver behind the persistent core inflation in Nigeria.

This is according to a study by Eric Ismail Otoakhia of the Department of Economics, Faculty of Business School, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, which was published in the latest edition of Bullion, a publication of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN).

Titled ‘Do Fuel Subsidy Shocks Prolong Price Instability in Nigeria?’, the study delves into the economic repercussions of Nigeria’s approach to handling fuel subsidies. The paper rigorously examines the ripple effects that follow the removal of fuel subsidies on the nation’s price levels from December 1996 to August 2023. By adopting a dynamic autoregressive model, the study aims to quantify the impacts of these changes on economic stability.

Subsidy reforms counterproductive to cost of living stability

The findings pointed to the counterproductive effects of subsidy reforms on the cost of living, highlighting the challenges faced by fiscal and monetary policy coordination in ensuring economic stability.

The study read:

- “The removal of such subsidies, when accompanied by income redistribution and increased government spending on public investments, inevitably leads to a persistent increase in the price level.

- “The findings of this paper have shown that government actions in handling fuel subsidies are counterproductive to fiscal and monetary policy coordination in ensuring a stable cost of living.”

The study, however, noted that fuel subsidies have been a double-edged sword, offering relief against the rising cost of living by stabilizing fuel prices, yet posing sustainability challenges amidst Nigeria’s significant infrastructure needs and escalating debt levels.

The money supply effect

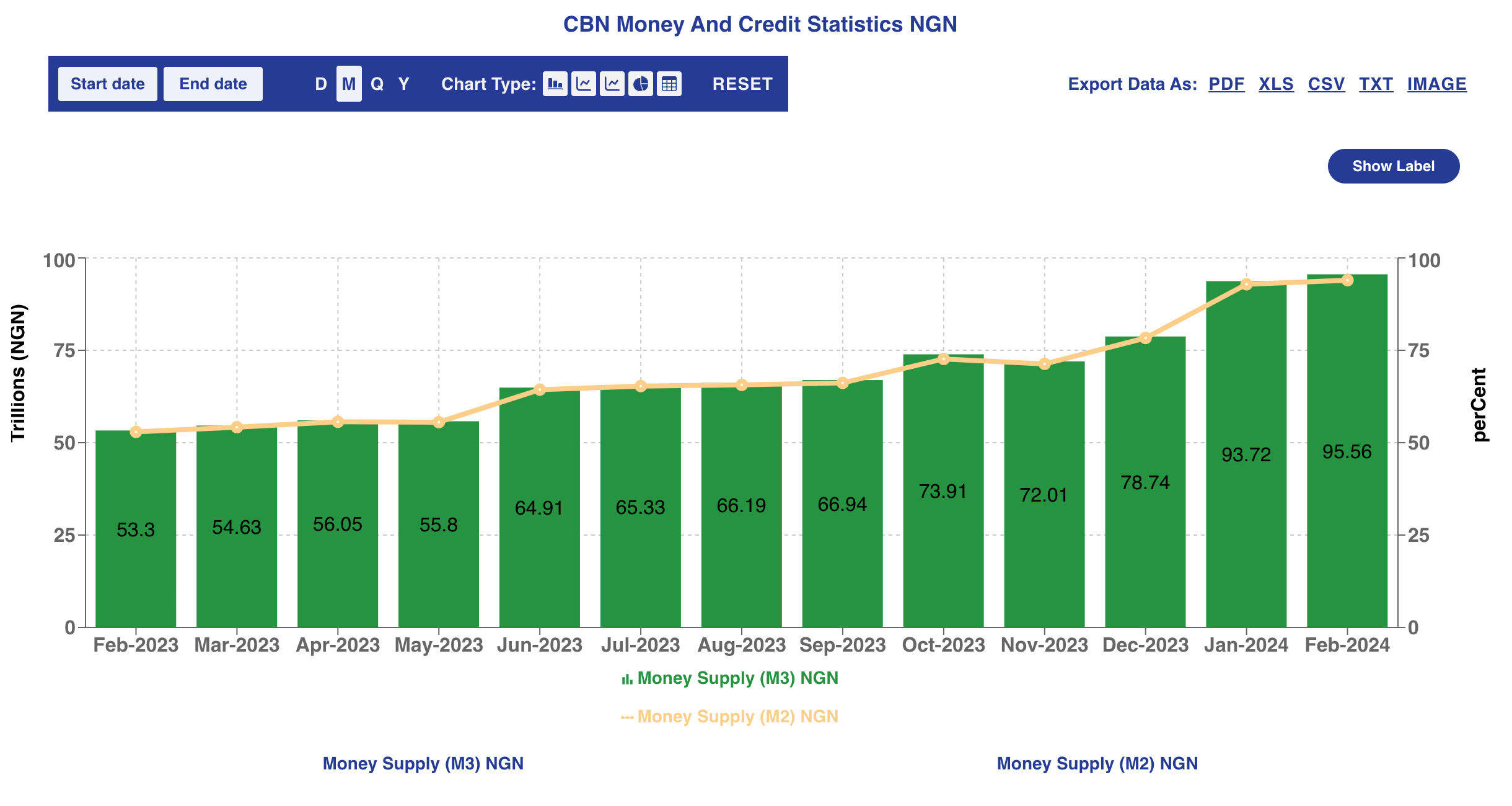

Nigeria’s broad money supply (M3) surged to a new historic high of N95.56 trillion as of February 2024 despite the hawkish tightening stance of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC). This figure represents a staggering 79.29% surge from the N53.3 trillion recorded in February 2023, showcasing a substantial year-on-year growth of N42.26 trillion.

The study, however, noted that increase in the money supply does not trigger significant and prolonged rises in inflation, suggesting that phasing out fuel subsidies introduces greater risks to economic balance.

The study added:

- “The results reveal a prolonged increase in inflation rates following a positive shock to the positive semivariance of fuel prices, indicating that fuel subsidy reforms disrupt price levels and impede fiscal-monetary policy coordination to achieve price stability.

- “In contrast, a positive shock to the money supply does not result in a significant and extended rise in inflation rates. This suggests that eliminating fuel subsidies poses a greater risk to price stability.”

The weakness in cash transfers

The World Bank recently said that cash transfers can help save Nigerians from intergenerational poverty traps as inflation and low economic growth adversely affect the poor. Also, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) emphasised the need for the Nigerian government to prioritise the full implementation of its cash transfer program to aid vulnerable households. This step is crucial before the government takes on the task of revaluating the costly fuel and electricity subsidies.

The paper, however, warns against depending solely on income transfers as a solution to the adverse effects of subsidy removal, given the government’s fiscal constraints. It recommends exploring alternative subsidy approaches, like agricultural subsidies, to promote food security and support the agricultural sector, offering a more viable and sustainable solution for economic stability.

The study noted:

- “If the current administration successfully eliminates fuel subsidies, relying solely on income transfers will not provide long-term stability in the cost of living.

- “These transfers are unsustainable given the current fiscal constraints of the government. Instead, an alternative subsidy approach, such as agricultural subsidies that encourage farmers and promote food security, may be more viable.”

The fuel tax option

The research proposes a novel approach to manage the economic implications of subsidy removal. Rather than erratic withdrawal of fuel subsidies, it suggests the implementation of a fuel tax targeting non-commercial vehicles. Such a measure would not only foster energy efficiency but also contribute to reducing CO2 emissions, aligning with global environmental objectives.

The study concludes that removing fuel subsidies leads to unmanageable increases in the inflation rate, with core inflation especially sensitive to such governmental energy reforms. The analysis criticizes the government’s recurrent attempts to remove subsidies as detrimental to the broader goal of macroeconomic stability.

Proposing a shift in subsidy strategy, the research advocates for funding subsidies through direct taxes on private, non-commercial vehicles. This strategy could expand the government’s tax revenue and correct the market failures associated with prolonged energy subsidies.

Interesting paper, but there is a massive confounding variable that this paper does not address, which is the fact that global oil prices inherently play a significant role in shaping the dynamics of fuel subsidy policies and their economic impacts.

When global oil prices rise, the cost of maintaining fuel subsidies increases, placing a heavier fiscal burden on the government. This can lead to more significant subsidy removals or reductions, which directly impacts domestic fuel prices and inflation.

Second, High global oil prices can independently contribute to inflation by increasing the cost of imported goods because of the higher cost of transport and production faced by international producers who do not have access to subsidized energy costs.

Third, volatile oil prices can lead to economic instability, affecting consumer spending, investment, and government spending—all of which can influence inflation rates independently of fuel subsidy policies.

It would be interesting to see this analysis redone, but with global oil prices controlled for and isolated as an additional explanatory variable in the ARDL framework.