In an exposè after her exit as the Minister of Petroleum resources, the infamous Madam Diezani Alison-Madueke once described the “business of oil as a rollercoaster”. Just like the prices of the underlying commodities, the oil and gas industry is volatile.

It is the rendezvous of Murphy’s law and Sod’s law. Stakeholders would agree that you are one event from capitulating. It could either come from a petroleum law, a regulatory change, or from political instability, community agitation, or an accidental British Petroleum-esque spill, or worse, a malfunction that could cost severe losses in infrastructure or lives; and in recent times, opposition from climate change activists.

And even if you escape the aforementioned human factors, you are left with an ‘Act of God’ that can cause a helpless force majeure. But despite the potential risks, the oil and gas industry is where you find only the richest of oligarchs – because the higher the risk, the higher the probability of reward. Only an elite few participate in this industry, hence its contribution of less than 8% of Nigeria’s GDP despite being the country’s major resource.

Two interesting oil ventures are taking place in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry. One, Dangote’s daring construction of Africa’s largest petrochemical refinery and more recently, Seplat’s acquisition of Exxon Mobil’s shallow water business in Nigeria. Both companies stand to earn a huge chunk of fortune with their ambitious undertakings, all things being equal, albeit all things are never equal in oil and gas. Admittedly, the headline and introduction might suggest a cynical perception of Seplat’s acquisition of Exxon’s assets, however, this article just seeks to pose an inquiry on the details, risks, and benefits of this acquisition.

There have been calls for domestic private industry players to expand in the industry to safeguard the interests of Nigeria’s energy development and economy. There is a 25-page document that takes a stab at illustrating Seplat’s rationale behind their $1.283 billion-plus an extra contingent payment of up to $300 million to acquire the entire share capital of Mobil Producing Nigeria Unlimited (MPNU) from US supermajor Exxon Mobil.

From that breakdown, we can see the following strategic rationale behind the transformational acquisition. The purchase:

- Established high-quality, operated assets delivering strong cash flow from existing US-based production.

- Upside potential from an extensive portfolio of low-cost and low-risk production optimization opportunities.

- Significant undeveloped gas resource base to underpin energy transition and drive domestic and export revenues when developed.

- Portfolio diversification through entry to shallow water, with dedicated export routes offering enhanced security.

- Reinforces balanced approach to gas and oil in their portfolio.

- Disciplined investment, conservative assumptions, and attractive metrics that enhance dividend potential.

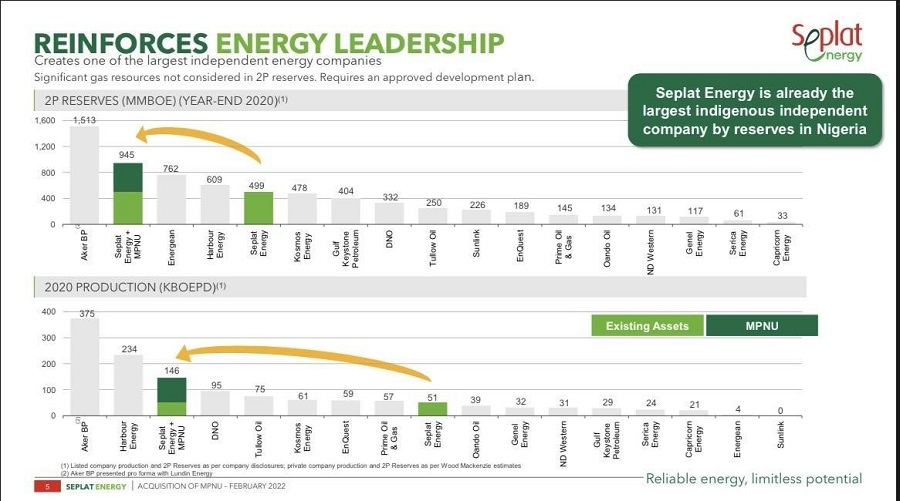

The above would reinforce Seplat’s energy leadership because, prior to the deal, the Nigerian-based company was already the largest indigenous independent company by reserves in Nigeria. Page 5 of the “Acquisition of MPNU” document, shows that the move significantly boosted their portfolio. The stock market responded to this bullishly as Seplat shares led gainers in the Nigerian stock exchange with a 9.99% increase during the day. The deal will drive growth and deliver value for all stakeholders.

Exciting times are ahead for Seplat and Nigeria but it would be remiss to ignore the challenges Exxon Mobil encountered while owning these assets. Exxon Mobil, one of the top 10 largest companies in the United States issued a statement saying “This sale will allow us to prioritise competitively advantaged investments in our strategic assets”. What this can be interpreted to mean is “these assets we have sold are comparatively not as beneficial to our portfolio as other strategic investments we have”. Therefore, this sale looks like another sign of the retreat by major international oil companies (IOCs) from certain Nigerian projects following years of spills and other disruptions including pressure from shareholders and investors to invest in cleaner forms of energy.

There are insider theories that say the gross profits to assets ratio or returns on the sold assets were declining as some of the oil fields were not producing the same levels as they did decades ago. But page 8 of the Acquisition document highlights how the Offshore infrastructure offers dedicated and secure export routes with a strong track record of operating uptime of 86% (2011-2020) and minimal reconciliation losses. This is certainly the bigger picture in the eyes of Seplat’s stakeholders. Leveraging this would be a masterstroke for Seplat stakeholders.

Globally, on an Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance front, there is a shift of investment from fossil fuel to cleaner forms of energy. Shale oil companies in the United States have been crying out because of a lack of CAPEX (Capital expenditure), so for Seplat to pull this financing off with international capital providers is highly commendable. Seplat’s mission is to “lead Nigeria’s energy transition with accessible, affordable and reliable energy that drives social and economic prosperity”. The acquisition would help them deliver this transition.

Conclusively, for Seplat to get maximum value for their deal, they need strong government support and backing. Roping in NNPC into the Joint Venture would possibly ensure that. The government also needs to provide an enabling business environment and expedite approval processes for the company. Since this is the first transaction since the new Petroleum Industry Act – the government should be committed to showing the new Act has brought about dividends to the energy sector. Perhaps, lobbying would be easier as the company is “one of their own” and the management understands the Nigerian business terrain.

The acquisition comes at the back of Nigeria’s receding production output and foreign investors’ exit, so it is evident that Seplat Energy is taking a huge risk. Foreign investment exits are a bad indicator. Domestic players need support. The Nigerian government should not see this acquisition as a “get out of jail” card for them but a second chance to fix existing issues in the oil and gas regions that are making the oil and gas business turbulent.