Since the presidential media chat there has been a considerable storm over the President Muhammadu Buhari’s no retreat no surrender mantra over naira devaluation. Clearly the president’s position informs a similar intransigence by the Central Bank of Nigeria which has elected to implement various demand management measures instead of having a third bite at the devaluation cherry.

In a related development, talk has switched from devaluation to full floating of the naira. Well as ever in debates over economics, the issue is that a lot of people against devaluation do not want to go back to school and study economics again. In essence floating the naira now and devaluing now are both the same thing but let’s keep that from the accountants, lawyers, doctors, non-economists who like to argue with followers of the dismal science.

I will try to keep it in simple demand and supply terms to explain the issues with the naira. In secondary school we were taught the basic laws of demand and supply – price is inversely related to quantity demanded but directly related to quantity supplied. If there is a scarcity price should go up to clear the market and if there is a surplus price will tank.

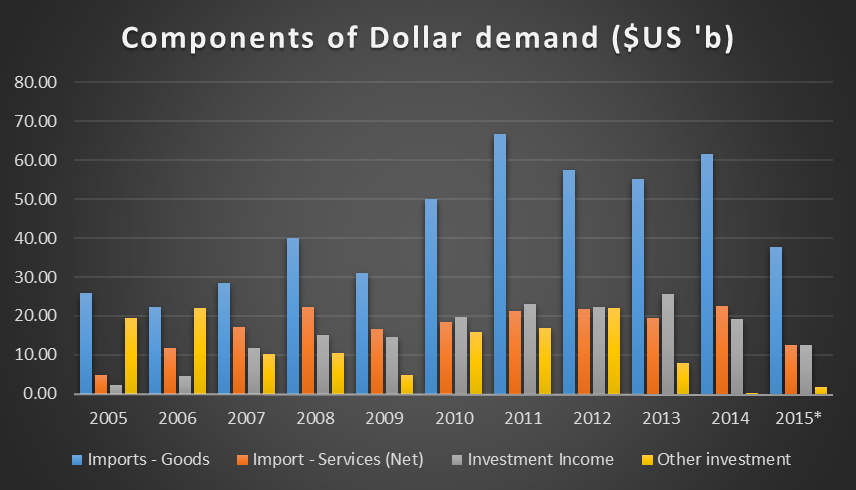

The foreign exchange market works on the same principle just that we call a lot of things differently in the market. On the demand side, people demand dollars in Nigeria for a lot of reasons which can be summarized as for imports of goods and services. In addition, dollars are demanded for repatriation by investors in Nigerian assets and other investment. For example when foreign companies invest in Nigeria anytime they make profits they have to repatriate back some of it as dividends back to their overseas country in the same way if a Nigerian buys shares of Apple he/she gets paid back on profits.

On the supply side, the key source of inflows are exports which in Nigeria is dominated by oil exports which contribute over 90% of exports. In addition, you also have things such as remittances and foreign investment flows (direct investment and portfolio investment) which is dollars brought by foreigners to invest either on public or private companies. Lastly, Nigerians living abroad sometimes send money back home to their families via remittances.

Now the CBN is a very good organization more than any other government bureaucracy they keep data on both the demand and supply side of dollars. So I put together the data for these two strands of the market from the balance of payment to make it easy to understand for the layman.

Chart 1

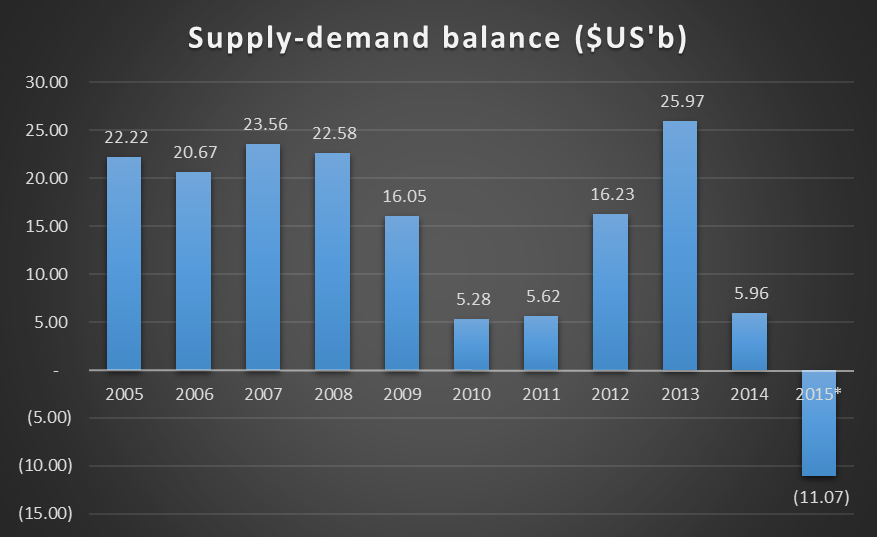

Chart 2

From the two graphs dollar demand has been rising overtime on account of growing import demand of goods and services. On the deficit side, Nigeria is a net services importer which given that the largest sector of our economy is services suggests a lot of that growth has been largely from using foreign inputs. On the supply side the dominant force is exports and the periods of drops in 2009, 2014 and 2015 coincide with naira pressures.

Now adding up both demand and supply components we have a state of play of what the entire market looks like. Before looking at the graph, note that Nigeria devalued in 2009, 2011, 2014 and 2015.

Chart 3:

From the shortfall graph it’s obvious that periods when there’s a mismatch the CBN moves the price higher to compensate for the disequilibrium between demand and supply. So it is pretty clear what happens as in elementary economics when demand exceeds supply and a scarcity exists the price moves up. In currency market, the naira exchange rate to the dollar goes higher. Under a managed floating regime the adjustment is called a devaluation. Under a full floating regime that adjustment is automatic and it’s called depreciation.

Nigeria operates a managed float regime as a number of EM economies. Under this regime demand and supply shortfalls do not necessarily lead to currency adjustments as the central bank steps in using its reserves to meet the supply shortfall. This is because the new equilibrium price might be undesirable or the factors causing it temporary, in which case using reserves to calm things is a good idea. Unfortunately, when economic agents suspect the central bank’s ability to support the FX is in doubt i.e. the currency defense is not sustainable, they rush to front load demand via all sorts of means. Often times, these actions keep the shortfall intact till eventually the price adjusts higher and speculators make their profits and the balance is restored. The problem in 2015 is that oil prices have fallen for a structural reason and are likely to stay low for a while which impairs the ability of the central bank to meet the gap.

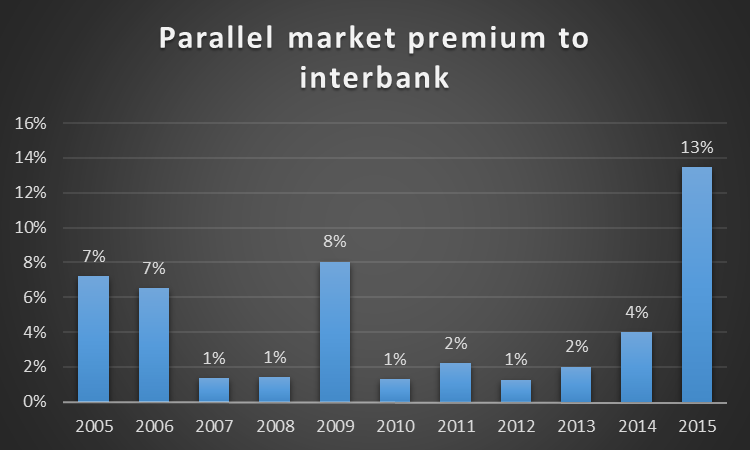

The data from the above is clear there should be a price adjustment call it whatever name: 1USD is not worth 200 naira. Resorting to demand management only complicates the problem leaving the misalignment intact for longer only drives more agents taking the other side of the transaction. I leave you with one more graph: the average premium of the parallel market over the interbank. If this chart does not convince you that the naira is mispriced at the current level nothing else will.

Note:

All data sourced from the CBN statistics bulletin

Asterisk means data for 2015 is for first three quarters.

Great write up. Nairametrics is now one of my first point of reference for updates on business in Nigeria

Thanks a lot

i do disagree with this analysis.there is another way of seeing things.it’s true the supply of anything affects.i.e if the supply of money exceeds the means of production.leads to inflation.IT COULD BE MORE POSSIBLE THAT THE SUPPLY OF MONEY IS AFFECTING THE VALUE OF THE NAIRA NOW.FOR DECADES THE FED. GOVT HAVE BEEN OPERATING DEFICITS, AND THE INABILITY OF THE C.B.N IN MOPING THE NAIRA BY ANY MEANS.The central bank of nigeria have been very negligent in managing or helping the supply of money.

In high school in nigeria,we are thought,that the c.b.n can uses a direct means to control the supply of money i.e they can debit the banks directly,by fiat,now we are reading m.r.r.which is a merely a technical terms.

It’s true that oil export is being used of 90% of our foreign reserve.WHOSE FAULT IS IT ?.IT’S THE CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA AND THE MINISTRY OF FINANCE.if they want to use export by alternative means,they can do it if they chooses.i.e manufacturing

With 6 months.nigeria can increases the nigerian foreign reserves,and create unlimited foreign reserves within 6 weeks.IF IT HAPPENS THIS WAY THIS SUPPLY AND DEMAND OR FOREIGN CURRENCY WILL BE A THING OF THE PAST.IT IS A SIGN OF MENTAL LAZINESS IN NIGERIAN VARIOUS DEPARTMENTS.

iT is more than possible to uses $2 billion to gets $50 billion within 6 weeksnow foreign reserves which was more than $ 70 billion at one time under obasanjo due to increases in oil prices is now about $29 billions as at today.Why not uses one bank to create dollar secured bond.they can sell this bond with a redeemable return of about 13 %,sold in batches of $500,brokers can buy to the tune of $ 1 million, other banks can buy to the tune of $10 million.the c.b.n can buy the shortfall.if you repeat this exercise as the banks want it, or the c.b.n do it.

The plan is to create liquidity,so i do not see any problem here and there.

Wrong for poor to subsidize the rich in Nigeria, the foreign exchange rate set in Nigeria corruption period,the spread between buying and selling not sustainable, there should be only 2 Naira between buying and selling to stop speculators and banks using foreign exchange funds to shore up their capital base period.The spread of 50 Naira between buying and selling put unnecessary pressure on Naira. Let fix the exchange rate realistically period.