Early in March 2025, I sat amidst a group of executives in a sleek conference room in Europe. Eager to learn about Africa’s digital market, they threw question upon question at me, but one of their questions, seemingly easy in nature, stood out for me as one question with the most complex answer: “What does your market need?”.

I began to explain, sharing data, real-life use cases, and insights drawn from Nigerian consumers.

But as I spoke, I could already sense the familiar gap widening. This was not a situation that they could easily understand; the uniqueness and complexity of it all was too much, and so even though they nodded politely, one of them soon countered with: “In Latin America, we used this solution, and it worked perfectly”. In sombre silence, I considered their assumption that all emerging markets are the same; that what worked in São Paulo will somehow work in Lagos.

In reality, it does not work that way. Africa is not one big, uniform market. Nigeria is different from Ghana, just as Kenya’s tech ecosystem does not mirror that of South Africa’s. Each country in Africa has its own unique complexities, including regulatory environment, consumer behaviour, and economic reality. Yet, time and again, I find myself in boardrooms and public sector meetings explaining the same thing: that context matters.

You cannot simply copy and paste a business model from Latin America or Europe and expect it to thrive or have the same outcomes in Lagos or Accra. What works elsewhere might fail here, not because Africa is behind, but because it is different. And in that difference lies an opportunity.

But first, what makes the difference? In my opinion, there are four main indicators: Infrastructure, Regulation, Usage and adoption, and Affordability.

Infrastructure is the backbone of any digital space, whether broadband, broadcast, or banking technology. In the western world, these systems already exist and are very optimal, but in many African countries, we are still building or optimizing them, often through public-private partnerships and creative collaborations. Without reliable power or internet, even the most brilliant fintech or satellite solution cannot scale.

The African Development Bank estimated that Africa needs over $100 billion annually in infrastructure investment to close this gap. So before we ask why digital adoption lags, we must start there. The real conversation about digital growth does not start with innovation; it starts with infrastructure.

While infrastructure lays the groundwork, regulation determines how far and how safely innovation can go. Regulation almost always trails innovation, but in emerging markets, the gap between these two is especially wide. During my time working in Ghana, I remember watching regulators struggle with social media platforms that had no local/physical presence.

How do you regulate an entity that exists only in the cloud, with no physical address? How do you enforce national rules on a company that exists entirely online? You cannot revoke a license that they never needed.

However, progress is now being made. African countries like Kenya and Nigeria are now introducing regulatory sandboxes, where fintech products can be tested safely before rollout; a model that has been fully endorsed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for balancing innovation and consumer protection.

Beyond infrastructure and regulation, the usage and adoption of digital technology are another crucial factor. How Africans use technology is as diverse as the continent itself. Netflix, for example, initially tried to penetrate African markets using credit card-only payments. In Ghana, where fewer than 5 million adults out of the total 15 million adults had cards, that strategy was bound to fail, and it did not take long before this strategy failed.

Eventually, Netflix adjusted their strategy, adding mobile money and telco billing options. Only then did adoption rise.

The key lesson here is that even something considered minor can make or break a product, including the payment gateway. According to the Global System for Mobile Communications Association (GSMA), Africa now has over 400 million active mobile money accounts, and this is clear proof that success depends not on applying global assumptions, but rather on understanding local behaviour.

Likewise, the important factor is affordability. Interestingly, sometimes, the issue is not always that people cannot afford a product at all; it is that they cannot pay for it all at once. Breaking products into smaller, more affordable offerings can make a huge difference to usage. Fast-moving consumer goods, for instance, brands selling milk, detergent, tomato paste, etc., understood this early on and started the smaller packaging of solutions or products. Telcos in Nigeria and Ghana soon followed suit.

By offering airtime for as little as one hundred naira (N100) or one Ghana cedi (1 GHC), they made connectivity accessible and adoption more widespread. The same logic applies to tech. A $20 monthly subscription might sound very affordable in New York, but it is a big ask in Ibadan. To reach mass markets, one must price and distribute for volume, not margin.

While the listed factors are all crucial, the place of awareness cannot be overemphasized. You cannot sell a solution that people do not understand or trust. And in tech, this is even more important. In reality, tech adoption in Africa can increase when it is localised and humanised; when users can see its relevance to their daily lives.

This is why financial inclusion campaigns, radio sensitisations, and community demos matter. A case in point is the successful adoption of the Safaricom mobile money due to their investment in educating users at the grassroots level.

In conclusion, Africa is not just a single, uniform market, but 54 unique markets, with different infrastructural levels, regulatory maturity, cultural behaviours, and spending patterns. Global companies miss the mark when they try to bring a “one-size-fits-all” solution because treating Africa as a single market overlooks the micro-dynamics that actually drive growth. The future of technology in Africa will belong to those who listen first; those who design for the user, not the spreadsheet.

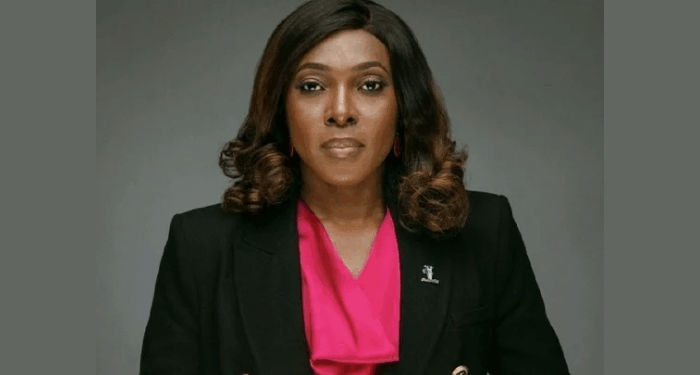

Jane Egerton-Idehen is the managing director/chief executive officer of Nigerian Communications Satellite Ltd. (NigComSat).