In December 1983, martial music began playing on the airwaves on the last day of the year followed by a speech by a stout Nigerian army officer, who later developed an affinity for dark goggles, announcing the dismissal of the Shagari regime. In the days that followed, Nigerians were introduced to their new head of state — an army officer with a stern reputation. In the months after he would impose a harsh economic doctrine bordering on mercantilism. So austere were the measures that an IMF officer wrote “… proved his independence by pushing through economic austerity so severe it went beyond what many advised — all the while he refused IMF assistance[1].

Did they work? Looking at GDP data during the period, on assumption of office in December 1983, GDP contracted 7.7% over the year — evidence of the ‘genius’ economic management skills of the Shagari administration. In 1984, the economy contracted, though mildly 1.1%. Even better by the time of stern general was ousted in August 1985, GDP expanded 8.8% over the first half of 1985.Surely He must be an economic genius right? Not quite, as the chart below shows a slight rebound in oil in 1984 helped limit the damage from his austere measures which kept non-oil growth negative.

[1] Mathew Martins (2002), Nigeria: Current Issues and Historical Background

Fast forward to 2016 and the stern officer is back, only this time in civilian garb and again his abilities are being tested and this time, even more so than the last. Why this long history lesson? The NBS is scheduled to release GDP numbers soon and given the backdrop of economic activities in the first quarter of 2016, anything short of a grim reading will cast strong doubts over the credibility of statistics bureau. Thus, the release should provide a storified version of the horror that low oil prices (and production), fiscal pussy-footing and incoherent monetary policy has wrought on the Nigerian economy.

Firstly, the oil GDP should extend its consistent contractionary trend following the spate of militant attacks which took out the 280kbpd Forcados crude oil pipeline in 1Q 2016. Furthermore, though global crude oil prices have staged a rebound, the first quarter average tracks below 2015 level. In effect the summary here is how low can oil

GDP contract. As ever, the issues dogging the sector remain — an inability to contain militancy and lack of meaningful progress on sector reforms which make investors wary about putting new money into the sector.

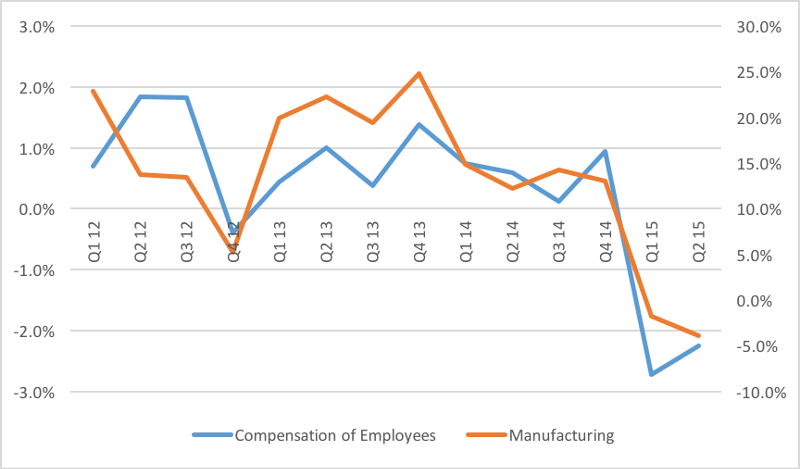

Wait a minute but since the GDP rebasing exercise, non-oil GDP share of total GDP has averaged 87%, so what is the fuss about a sector that’s not up to 15%. Though oil is less significant in economic activity, aftershocks from the sector percolate round the economy via the conduit pipe of government. Lower oil receipts transmit a contractionary shock to the economy via reduced FAAC allocations to the three levers of government with many state governments struggling to meet recurrent spending leading to salary backlogs. Interestingly, in wage growth in the first half of 2015, in real terms, was negative. As the chart below shows there’s real wage growth and manufacturing GDP seem to show strong co-movement.

Compensation to employees and Manufacturing GDP

Overlay this relationship with rising inflation, it’s easy to see why consumer purchasing power is largely restrained resulting in companies unable to clear product inventory. As sales pile up, I believe the NBS captures sales in manufacturing GDP, we should see a reversion to recession in manufacturing GDP after the one quarter swing in 4Q 2015. As if that was not enough, companies grappled with a power crisis in 2016 — a fallout of the increased Niger Delta militancy.

Other sectors are likely to slide further, for trade GDP, the refusal to be flexible on the currency (political correct speak for the d-word) which has led to a scarcity of dollars, should drive weakness in the sector. For construction GDP — no budget, no capex, states are broke and struggling private sector make it difficult to project anything short of continued recession. For services, the challenges are myriad but between FX issues, power challenges and slowing economic activity — snail speed growth is the likely outcome

Things get worse before they get better right? Probably not so quicky this time. Firstly oil GDP should tank further in over 2Q 2016 thanks to the motley crew of avengers, red egbesu water lions and other ridiculous sounding names trying to win the blow-a-pipeline competition. According to our minister of petroleum resources, these guys have pushed oil production down by 800kbpd — levels last seen under the General Sani Abacha. Cheer up at least you don’t have a dark goggled guy on all screens when you switch on the TV. Furthermore, following the theatrics of our minister of petroleum resources with last week’s deregulation, sorry price modulation (wherein naira was implicitly devalued), the CBN might actually ‘murder’ the naira soon to paraphrase President Buhari. Whether the CBN devalues, floats or whatever, markets have moved and more people are already devalued so consumption spending will remain depressed, firms will struggle to sell products shifting focus to ‘improving efficiency’ (political correctness for laying off). Unsurprisingly, unemployment is rising and the misery index worsening yet CBN insists on monetary policy tightening waving an elementary economics textbook argument about the need for a response to a fuel price driven inflationary surge. If anything, Mr Governor should save his tightening ammunition and fix the FX issues causing the current inflationary predicament rather than pursuing a scorched earth monetary policy. In any case if he thinks by telling us CBN is fighting inflation while pumping in money into the economy via all sorts of intervention programs at single digit interest rates is great economics, I plead the fifth and rest my case. As I said earlier real wage growth is negative there’s virtually no substance to a demand pull inflation argument.

In all as in 1983–85, history is repeating itself and while oil prices have recovered recently, the militancy unheard of in the 1980s, is wreaking havoc on oil GDP. President Buhari will have to rely less on luck this time and more on pragmatic policies as his petroleum minister is showing to give the economy a kick. Already by towing an expansionist part, the president is not repeating the austere doctrine of the 1980s. But what of the price hikes isn’t that austerity? come on we are liberalising (economic correctness for thatcherist policies) J

All in All the Nigerian economy is between a rock and a very hard place.