Key points

- Firstly, I do not support the sale of our stakes in the Joint Ventures. I prefer if the Joint Ventures were listed on the Nigerian bourse over the next five years.

- Secondly, I am in support of the government leaving operatorship and ownership of oil blocks to qualified oil companies, including its subsidiary NPDC to focus on taxation.

- I do not support the sale of the country’s stakes in the Joint Ventures for three clear reasons.

- What to do with the JVs

First Reason

First is the absolutely wrong timing of the sale. While the focus of arguments in support of the sale is based on the country’s inability to fund the overdue cash calls, the attractiveness of the blocks and its potential to generate a lot of revenues not enough attention is being given to the actual timing of the sale. Selling the stakes at a time when oil prices are depressed and our crude oil is being ignored by crude oil importers around the world, this perhaps isn’t the best of times to put more oil blocks on the global chopping board.

You may argue that the blocks have great value and oil companies would pay top dollars for those stakes but don’t say that among investment bankers. Surely, bankers will tell you that pricing discipline and operational efficiency is the order of the day but the valuations of the blocks have dropped significantly due to the drop in oil prices. Valuations will also have to include some risk element for the inability to dispose of the crude oil from these blocks in the global market.

Second Reason

I do not support the sale because there is absolutely no historical records to support the point that the revenues will be effectively used to diversify the economy and compensate future generations with other income sources equal to or surpassing the revenues they would have lost by this sale.

We have sold assets in the past, so this is not the first time. However, we what we have not done is to sell our stakes in the JVs. However, for all the privatization and efforts to get more private sector control of key sectors, we are yet to see a considerable diversification of exports or increase in income from other sources equal to the level of income currently being generated from the upstream sector.

Third reason

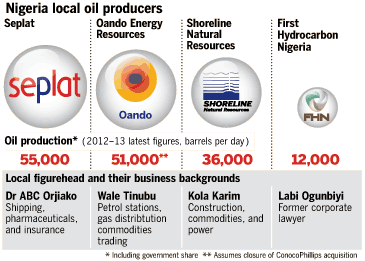

My third reason is why should it be the stakes in the JV specifically? Why not hold a licensing round for some of the actually very juicy marginal fields that have no major technical issues and license more local companies to produce from these fields? We have over 200 open blocks according to DPR data. Why not license a few more OPLs? If local oil companies are eager to develop expertise in the oil industry and help the government boost revenues, why cannibalize existing oil flows into their own balance sheets? Why not create new flows by taking over new fields – marginal fields even to avoid exploration costs on new blocks?

Point 4

Perhaps I should add a fourth reason. Can we guarantee that even if we sell down on these assets successfully for a good sum, the funds will not simply disappear into the labyrinth of revenue collection mechanism between the NNPC and the Federation Account or get diverted to debts to international lenders, contractors and outstanding public staff salaries? I don’t even want to worry about Labour reaction to this sale.

What to do with JVs?

So what do we do with the JVs? I think it’s quite clear. There are two major steps;

Step 1 – Starting from the funding argument, we need to start pre-allocating barrels to capex and not just royalties, cost recovery, taxes and profits. In most other climes, capital costs are pre-allocated before profits are shared thus ensuring that the fields are able to continue covering their costs and investment decisions can be taken as at when due. Following expansion in the national budget, and most especially fuel subsidies, the amount allocated to cash calls has reduced. This has been further strengthened by the development of the Modified Carry Arrangement, which is really just saying the IOCs should raise money to also cover NNPC’s share of the cash calls and recover it back before allocating barrels to the four items listed above previously.

While the MCA has enabled the oil companies continue development of their oil fields, it has restricted the flow of funds to exploration projects and also limited the pace of development of offshore fields, which are much more expensive. The amount of oil discoveries announced in Nigeria has declined significantly. Although the tendency among the IOCs now is no longer to announce their discoveries however their annual results show that reserve replacement in Nigeria remains quite low. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be a major news in 2014, when ExxonMobil announced that it had Large fields like the Egina, Erha North Phase 2, Bosi, Nsiko, Uge and several more are expected to add about 880 kbpd to Nigeria’s crude oil production in the next five years if they get developed. However, funding these developments will require huge amounts of capital that the NNPC may not be able to fund.

Step 2 – The second step is listing the JVs on the NSE . While it would be fantastic for the Nigerian bourse and investors on the exchange, the amount of restructuring required to achieve the level of corporate governance; financial accounting standards and transparency disclosures necessary for equity markets would give the consulting industry a boom year.

This is not to discredit the IOCs, most of which have very high standards of operations. However with the NNPC as the largest shareholder of these JVs and the level of corruption indicated by recent scandals, these JVs are not likely to be squeaky clean themselves. Very little is known about these joint ventures beyond what is published by the NNPC. However, it would give average Nigerians an opportunity to benefit from the industry that literally supports our economy and government.

It would help in further diversifying the NSE, which is currently split into three major groups, Dangote Cement (c. 30%), Banks (c. 30%) and others representing the balance of 40%. Listing on the local stock exchange would also attract some foreign investment to the NSE as foreign investors would be keen to participate in those companies and also share in the potential dividends.

You might ask if this isn’t the wrong time to divest stakes in the JVs to oil companies? Why should equity investors have a piece of the pie now? Wouldn’t the low valuation also mean that the company is worse off in the long run? I think not. Divesting to the equity market represents a shift of these cash flows from the government directly to the investors (people), which would enable the government focus more on taxation. The shares in the joint ventures would be allocated in such a manner to ensure both institutional and retail, foreign and local investors are able to get a share of the companies. Imagine the size of attendance at the AGMs of these companies. Whereas, selling them to the oil companies, most of which will seek foreign financing for the acquisition will take revenue away from our economy. Furthermore, the listing of these JVs will have to be phased out over a period of time, especially as oil prices recover. At present valuations, those JVs produce over 1.2 million bpd and could be worth over $30 billion. Thus, listing just 5% on the NSE this year would yield about $1.5 – 2 billion. If OML 29 was worth $2.58 billion, 5% of SPDC, which holds at least 13 OMLs, reserves of over 3 billion barrels and produces over 200,000 bpd should be worth a lot more, even at today’s depressed prices, especially when you factor in reserves.

Step 3 – My third point is quite simple. Government needs to exit ownership of oil blocks and move to a taxation-based system. Going by my arguments above, this doesn’t need to happen immediately. This doesn’t not mean the NPDC cannot own stakes in oilfields or blocks. The point here is under which type of agreements and how the government will generate revenues from its oil. For the NPDC it’s quite straightforward.

The NPDC should operate as a purely commercial operator owned by the government operating under the Production Sharing Contract. Thus, this will give the NPDC opportunity to divest stakes in its fields like any other oil company, raise funds on the capital markets via corporate bond issues. More effectively, the NPDC could get a borrowing base of about $5-10 billion to support its output expansion program. Government retains 100% ownership if it so chooses but the management of the company is by qualified industry professionals and like any other shareholder in a company, the government receives dividends at the end of the financial year.

This should constitute the government’s only direct exposure to the oil and gas industry. Otherwise, all oil blocks and fields should be licensed purely to oil companies under the production sharing contracts and the government should receive just rents, royalties and taxes from the oil companies. The pace at which the oil fields and blocks are developed will thus be dependent on the oil companies and not hampered by the inability of the government to fund its joint venture cash calls.

Furthermore, the focus on taxation instead of crude oil sales should yield further clarity on the government revenues from the oil industry as the larger companies are public entities and should publish the payments made to the government via their financials. Another key benefit of this system is in the collection as the taxes should rightly be paid to the Central Bank or directly to the Federation account, stripping out a key channel of corruption from the NNPC – direct access to revenue from sale of crude oil. With oil revenues likely to come from only taxes, the government will pay more attention to tax collection systems and ensure that all taxes are paid. Incentives such as the pioneer status will be granted as tax rebates not tax holidays.