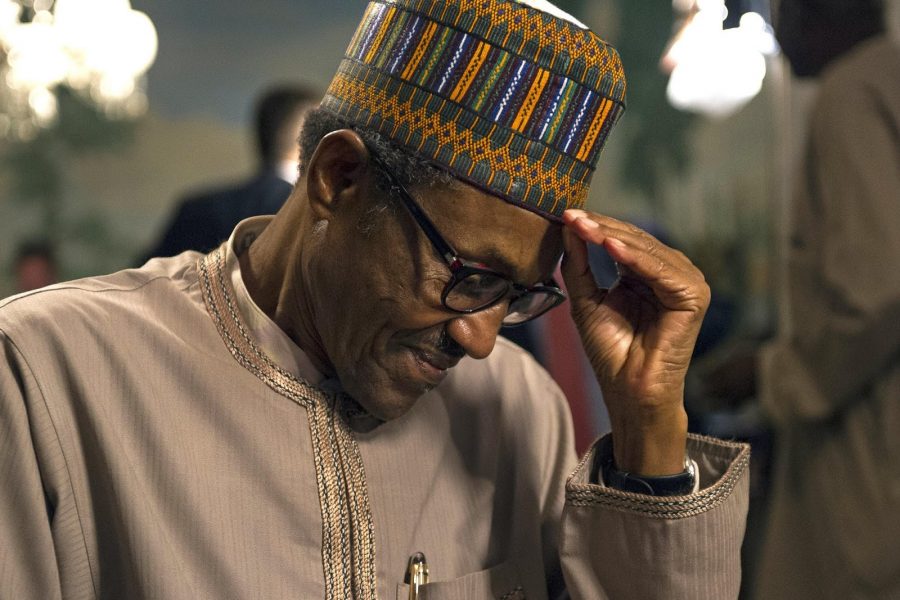

The COVID-19 pandemic has been nothing short of unfavourable to an already vulnerable Nigeria. The nation’s overdependence on oil, fragile infrastructure, low foreign and domestic investments, declining foreign reserves and debt crisis, has further tightened the expected economic consequence of the pandemic. It is also what is responsible for the recent revision of 2020’s budget. Last Friday, President Muhammadu Buhari signed into law a revised budget for the year 2020 of N10.8 trillion. Following the restrictions in international trade due to pandemic-induced lockdowns in many parts of the world, weakened global oil demand, as well as the pronounced decline in oil prices, the budget had to be revised to reflect current realities.

The GDP was projected to grow at 2.93% in 2020, but this has now been revised to -4.41%. For the revised budget, the oil benchmark was reduced from $57 per barrel to $28, and crude production was reduced from 2.18 million to 1.7 million barrels per day. Nigeria’s Minister of Finance, Zainab Ahmed revealed that the impact of these developments is a c.65% decline in projected net 2020 government revenues from the oil and gas sector. So far, Nigeria has been only able to meet 56% of its target revenue from January to May as the global oil price crash affected government revenue due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A budget deficit of N5.365 trillion is expected to be funded by domestic and foreign borrowing while direct revenue funding will cover N5.158 trillion.

READ MORE: G-20 central banks are considering ‘special’ debt swap deal for African countries

The debt situation

Data from the Debt Management Office (DMO) reveals that Nigeria’s total debt currently stands at N28.62 trillion. This is following the move by Fitch, in April, to downgrade Nigeria’s Long Term Foreign Currency Issuer Default Rating (IDR) to ‘B’ from ‘B+’ with a negative outlook. Mahmoud Harb, a director at Fitch had explained that the debt to revenue ratio for Nigeria is set to deteriorate further to 538% by the end of 2020, from 348% that it was a year earlier before improving slightly next year. While the Joint World Bank-IMF Debt Sustainability Framework for Low-Income Countries released in 2020, noted that a country’s debt service to revenue threshold should not exceed 23%, Nigeria’s debt service to revenue ratio for the past five years has witnessed a relatively steady increase. Analysis using data from CBN’s annual Statistical Bulletin reveals debt service-revenue ratio of 32.63% in 2015, 56.83% in 2017 and 43.62% in 2019. For the first quarter of 2020, we witnessed a 99% debt service to revenue ratio suggesting that almost all the revenue generated from both oil and non-oil sources was used to meet debt service obligations.

While this is reflective of the decline in oil revenue for the period, it is also one sign of our looming debt crisis. According to information contained in the recently approved revised budget, Nigeria spent N943.12 billion in debt service in the first quarter of the year and N1.2 trillion between January and May 2020. It also plans to spend N2.9 trillion on debt service in 2020 against a revenue of N5.3 trillion. This represents a 55% debt service to revenue ratio. About N1 trillion was spent on debt service in the first 5 months of the year.

If we were to strive to attain a palatable benchmark debt service to revenue ratio of even 25%, based on the projected debt service for 2020, the government will have to generate at least 11.6 trillion annually. The highest FG revenue witnessed over the past five years since 2015 was 2019’s N4.8 trillion. Even though some of the debts come with very little interest rates like the $3.4 billion loan under the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) at just a 1% rate of interest, the overall debt servicing burden is one that Nigeria may not be able to get itself out of especially since it cannot completely stop borrowing.

With oil projected to only increase marginally in the coming years from the $28 dip, the nation needs to look into harnessing non-oil revenues. However, because the non-oil sector requires that productivity is enhanced, it begs the question of whether the right infrastructures exist for us to make such demands of the sector.

What we have been spending on

Over the past 5 years spanning 2015 and 2019, the Nigerian government has spent about N34.8 trillion comprising of both recurrent and capital expenditures in the ratio of 73% in recurrent expenditure and only 19% in capital expenditure; the difference is attributable to transfers. What this means is that only about 19% of the debt load is what has been invested in further developing the nation through the creation of relevant infrastructure. The rest were spent on recurring expenses like salaries – a testament of the profligacy that thrives. Consequently, the funds being spent on debt servicing can be seen as another way of wasting limited resources while funding very little capital expenditure that could be used to stimulate the productivity of Nigerians.

While COVID-19 has revealed our overdependence on the oil sector as well as the inefficiencies that have left us in the quagmire of increasing debt and reducing revenue from known sources, the biggest slap comes from knowing that Nigeria as a nation has spent so much and achieved so little that it can bank on when the chips are down.